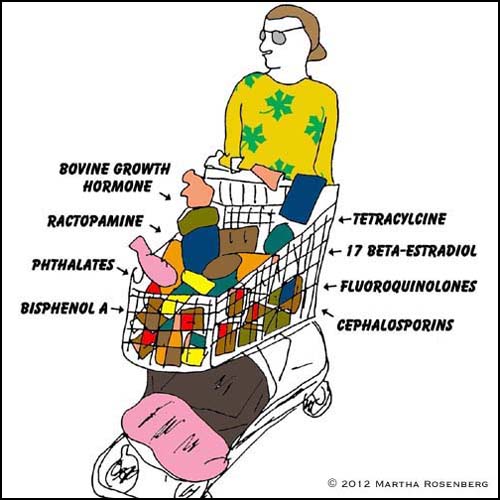

Endocrine disruptors, synthetic chemicals that mimic and interfere with natural hormones, lurk everywhere from canned foods and microwave popcorn bags to cosmetics and carpet-cleaning solutions. The chemicals, which include pesticides, fire retardants and plastics, are in thermal store receipts, antibacterial detergents and toothpaste (like Colgate’s Total with triclosan) and the plastic BPA which Washington state banned in baby bottles.

Endocrine disruptors are linked to breast cancer, infertility, low sperm counts, genital deformities, early puberty and diabetes in humans and alarming mutations in wildlife. They are also suspected in the epidemic of behavior and learning problems in children which has coincided, say many, with wide endocrine disruptors use.

Like Big Pharma, Big Chem holds tremendous sway at the FDA which gave the endocrine disruptor BPA a pass in March, citing “serious questions” about the applicability of damning animal studies to humans. But in April, research from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences presented new evidence of the ability of endocrine disruptors—in this case the pesticide chlorpyrifos, found in Dow’s Dursban—to harm developing fetuses. Janette Sherman, M.D., a pesticide expert and toxicologist, has studied the effects of chlorpyrifos for many years and talked about what her research has revealed.

Rosenberg: You published a paper in the European Journal of Oncology in 1999 which is eerily predictive of recent Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences research about children exposed in the womb to the pesticide chlorpyrifos (found in Dow’s Dursban and Lorsban). This research found actual structural changes in exposed children’s brains, especially related to emotion, attention and behavior control.

Sherman: Dursban (chlorpyrifos) is a pesticide manufactured by Dow Chemical Co. and Eli Lilly that has both organophosphate and tri-chlorinated pesticide characteristics and toxicities. Working as a legal consultant, I evaluated eight children with profound abnormalities whose families had proof of their child’s exposure to chlorpyrifos in the womb. I was stunned by how much the children resembled one another—they looked so similar they could have been siblings or cousins. The children were all severely retarded and needed feeding and diapering. One had quadriplegia and another died soon after I examined him.

Rosenberg: In your 1999 paper you refer to the brain problems cited in the Proceedings research as possibly pesticide-related.

Sherman: Yes. The children also had corpus callosum defects, which means there was no connection between their right and left side of their brains.

Rosenberg: Where were the children located and where did you examine them?

Sherman: The children were in Arkansas, on Long Island and in California. The use of Dursban occurred in the homes. Since Dursban has been restricted from home use [ed. in 2000] of concern are agricultural use of chlorpyrifos that continues and questions of birth defects in women agricultural workers. I examined some of the children in their homes. In other cases, the parents brought them to be examined, if they had vans equipped to move the children.

Rosenberg: In addition to the mental retardation, paralysis and structural brain problems you found deafness, cleft palate, eye cysts and low vision, nose, brain, heart, tooth and feet abnormalities and many sexual deformities.

Sherman: Yes, the sexual and reproductive defects included undescended testes, microphallus [tiny penis], fused labias [vaginal lips] and wide spread nipples. I also report in the paper, 13 adverse reproductive cases linked to chlorpyrifos from Dow’s own research database. (European Journal of Oncology, Vol. 4, n.6, pp 653–659 1999)

Rosenberg: Anyone who is aware of the effects of endocrine-disrupting pesticides on wildlife can’t help but think of the frogs reported with no penises in so many U.S. streams or the sexual abnormalities reported in both male and female birds and other animals.

Sherman: Yes, the children’s defects mirrored effects of endocrine disrupters seen in wildlife. They also mirrored Dow’s own rat studies which showed testicular and urogenital deformities, skull and sternebrae (part of breast bone) abnormalities and cleft palate in exposed animals, especially from in utero exposure to chlorpyrifos. (European Journal of Oncology, Vol. 4, n.6, pp 653–659 1999)

Rosenberg: Published studies, including your own, signaled safety problems with Dursban years earlier. The EPA’s own data found eight out of 10 adults and nine of 10 children had “measurable concentrations.” Dow paid $2 million for hiding Dursban’s risks from 1995 and 2003 in New York. But the pesticide was not banned for residential use until 2000 and, after it was banned, people were allowed to use remaining quantities. Why did the cases that you and others uncovered seem to have little effect?

Sherman: Dow attorneys took my deposition for four eight-hour days in the mid 1990s and I supplied over 10,000 pages of medical records, depositions, EPA documents, patent information and toxicology studies on which I based my opinion. Even though genetic analyses were conducted for the paper and genetic causes for the defects were ruled out—siblings who were not exposed to chlorpyrifos, for example, were normal—Dow termed the cases genetic and was able to stop most, if not all, chlorpyrifos birth defect suits.

Dow has almost unlimited money and personnel to fight families and small-town attorneys and they send multiple personnel to the EPA to argue their side. There is also no penalty for withholding information.

Rosenberg: Dow claimed there was insufficient proof of chlorpyrifos exposure.

Sherman: Yes and one of the ironies, that I have cited in several papers, is that monitoring data for pesticide levels, either at the time of application or at the time of birth, is simply not done. People have no records and no way of collecting records of pesticides they have been exposed to.

Rosenberg: Lorsban, the agricultural version of Dursban, is still widely in use in crops like apples, corn, soybeans, wheat, nuts, grapes, citrus and other fruit and vegetables. Virginia Rauh, Ph.D, the author of the recent Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences paper, cautioned pregnant women to seek organic produce to avoid chlorpyrifos.

Sherman: I believe farm workers and pregnant women are at risk and obviously, a pesticide that is used widely in crops will also get in the drinking water. I don’t know how widespread chlorpyrifos use is overseas and in poor countries but the same risks apply.

Rosenberg: You have not been one to shrink from doing battle with Dow and other giant chemical companies. You write in one paper, “Dow has been reluctant to accept that exposure to a chlorinated organophosphate chemical designed to kill insects by interfering with neurological function could harm the developing human.” That’s pretty direct.

Sherman: Dow works powerfully against criticism. During one legal proceeding, I overheard a Dow attorney say, “This is the last deposition Sherman will appear at.” It takes nerve to go up against them.

Rosenberg: Before medical school, you worked for the Atomic Energy Commission and at the U. S. Navy Radiological Laboratory. But now you publish outspoken books and papers about radiation poisoning related to Chernobyl, Fukushima and other sources. What shaped your medical career?

Sherman: In the 1970s, I began doing worker compensation cases involving people working in foundries and I began to see a high incidence of lung disease. When the occupational medicine department at my university told me the information was anecdotal and there were not enough cases to be statistically significant, I sent the information to former Senator Phil Hart (D-Mich) who was working with the consumer advocate Ralph Nader at the time. Soon, the information I had uncovered was on the front page of the New York Times and I began to be flooded with information and requests from people who had knowledge of other apparent environment toxicity cases. I became specialized in toxicology and continue to cover environmental hazards presented by radiation, chemicals and pesticides like Dursban.

Rosenberg: Since Dursban’s ban, there have been calls for a Lorsban ban because of its effects on farm workers. In India, Dow’s offices were raided by Indian authorities for allegedly bribing officials to allow chlorpyrifos to be sold in the country. (Dow bought the Union Carbide plant in India where the 1984 Bhopal gas leak occurred.) And In 2008, the National Marine Fisheries Service sought chlorpyrifos restrictions because of dangerous levels seen in Pacific salmon and steelhead. Yet, like DDT, there have been calls to bring Dursban back into wider use—especially when bedbug infestations hit major cities.

Sherman: Well, with many of these harmful chemicals, you need to follow the money. In some. cases companies making harmful chemicals are even making drugs to treat their effects, like anti-cancer drugs. But consumers are not off the hook either, because we fail to ask questions, pay attention and read the fine print! END

Janette Sherman, MD specializes in internal medicine and toxicology with an emphasis on chemicals and nuclear radiation that cause illness, including cancer and birth defects.

Martha Rosenberg’s top selling health policy book, Born with a Junk Food Deficiency, was released in April by Prometheus Books. She is a freelance writer and editorial cartoonist. She has been a frequent contributor to the San Francisco Chronicle, the Providence Journal, and the Chicago Tribune. She has also contributed to the Boston Globe, the Los Angeles Times, Newsday, Arizona Republic, the New Orleans Times-Picayune, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, and Consumers Digest. In addition, she is a regular health columnist on the Huffington Post, AlterNet, Intrepid Report, CounterPunch, BuzzFlash, Foodconsumer, NewsBlaze, YubaNet, Scoop, and the Epoch Times.

Martha Rosenberg’s top selling health policy book, Born with a Junk Food Deficiency, was released in April by Prometheus Books. She is a freelance writer and editorial cartoonist. She has been a frequent contributor to the San Francisco Chronicle, the Providence Journal, and the Chicago Tribune. She has also contributed to the Boston Globe, the Los Angeles Times, Newsday, Arizona Republic, the New Orleans Times-Picayune, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, and Consumers Digest. In addition, she is a regular health columnist on the Huffington Post, AlterNet, Intrepid Report, CounterPunch, BuzzFlash, Foodconsumer, NewsBlaze, YubaNet, Scoop, and the Epoch Times.