To listen to the Republican candidates’ debate last month, one would think that President Obama had slashed the U.S. military budget and left our country defenseless. Nothing could be further off the mark. There are real weaknesses in Obama’s foreign policy, but a lack of funding for weapons and war is not one of them. President Obama has in fact been responsible for the largest U.S. military budget since the Second World War, as is well documented in the U.S. Department of Defense’s annual “Green Book.”

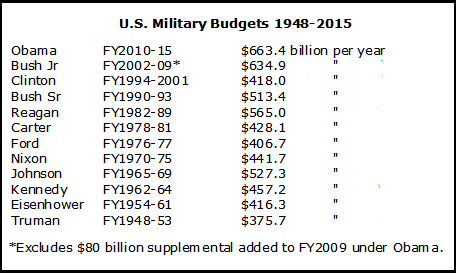

The table below compares average annual Pentagon budgets under every president since Truman, using “constant dollar” figures from the FY2016 Green Book. I’ll use these same inflation-adjusted figures throughout this article, to make sure I’m always comparing “apples to apples”. These figures do not include additional military-related spending by the VA, CIA, Homeland Security, Energy, Justice or State Departments, nor interest payments on past military spending, which combine to raise the true cost of U.S. militarism to about $1.3 trillion per year, or one thirteenth of the U.S. economy.

The U.S. military receives more generous funding than the rest of the 10 largest militaries in the world combined (China, Saudi Arabia, Russia, U.K., France, Japan, India, Germany & South Korea). And yet, despite the chaos and violence of the past 15 years, the Republican candidates seem oblivious to the dangers of one country wielding such massive and disproportionate military power.

On the Democratic side, even Senator Bernie Sanders has not said how much he would cut military spending. But Sanders regularly votes against the authorization bills for these record military budgets, condemning this wholesale diversion of resources from real human needs and insisting that war should be a “last resort”.

Sanders’ votes to attack Yugoslavia in 1999 and Afghanistan in 2001, while the UN Charter prohibits such unilateral uses of force, do raise troubling questions about exactly what he means by a “last resort.” As his aide Jeremy Brecher asked Sanders in his resignation letter over his Yugoslavia vote, “Is there a moral limit to the military violence that you are willing to participate in or support? Where does that limit lie? And when that limit has been reached, what action will you take?” Many Americans are eager to hear Sanders flesh out a coherent commitment to peace, diplomacy and disarmament to match his commitment to economic justice.

When President Obama took office, Congressman Barney Frank immediately called for a 25% cut in military spending. Instead, the new president obtained an $80 billion supplemental to the FY2009 budget to fund his escalation of the war in Afghanistan, and his first full military budget (FY2010) was $761 billion, within $3.4 billion of the $764.3 billion post-WWII record set by President Bush in FY2008.

The Sustainable Defense Task Force, commissioned by Congressman Frank and bipartisan Members of Congress in 2010, called for $960 billion in cuts from the projected military budget over the next 10 years. Jill Stein of the Green Party and Rocky Anderson of the Justice Party called for a 50% cut in U.S. military spending in their 2012 presidential campaigns. That seems radical at first glance, but a 50% cut in the FY2012 budget would only have been a 13% cut from what President Clinton spent in FY1998.

Clinton’s $399 billion FY1998 military budget was the nearest we came to realizing the “peace dividend” promised at the end of the Cold War. But that didn’t even breach the Cold War baseline of $393 billion established after the Korean War (FY1954) and settled on again after the Vietnam War (FY1975). The largely unrecognized tragedy of today’s world is that we allowed the “peace dividend” to be trumped by what Carl Conetta of the Project on Defense Alternatives calls the “power dividend”, the desire of military-industrial interests to take advantage of the collapse of the U.S.S.R. to consolidate global U.S. military power.

The triumph of the “power dividend” over the “peace dividend” was driven by some of the most powerful vested interests in history. But at each step, there were alternatives to war, weapons production and global military expansion.

At a Senate Budget Committee hearing in December 1989, former Defense Secretary Robert McNamara and Assistant Secretary Lawrence Korb, a Democrat and a Republican, testified that the FY1990 $542 billion Pentagon budget could be cut by half over the next 10 years to leave us with a new post-Cold War baseline military budget of $270 billion, 60% less than President Obama has spent and 20% below what even Jill Stein and Rocky Anderson called for.

There was significant opposition to the First Gulf War—22 Senators and 183 Reps voted against it, including Bernie Sanders—but not enough to stop the march to war. The war became a model for future U.S.-led wars and served as a marketing display for a new generation of U.S. weapons. After treating the public to endless bombsight videos of “smart bombs” making “surgical strikes”, U.S. officials eventually admitted that such “precision” weapons were only 7% of the bombs and missiles raining down on Iraq. The rest were good old-fashioned carpet-bombing, but the mass slaughter of Iraqis was not part of the marketing campaign. When the bombing stopped, U.S. pilots were ordered to fly straight from Kuwait to the Paris Air Show, and the next three years set new records for U.S. weapons exports.

Presidents Bush and Clinton made significant cuts in military spending between 1992 and 1994, but the reductions shrank to 1-3% per year between 1995 and 1998 and the budget started rising again in 1999. Meanwhile, U.S. officials crafted new rationalizations for the use of U.S. military force to lay the ideological groundwork for future wars. Untested and highly questionable claims that more aggressive U.S. use of force could have prevented the genocide in Rwanda or civil war in Yugoslavia have served to justify the use of force elsewhere ever since, with universally catastrophic results. Neoconservatives went even further and claimed that seizing the post-Cold War power dividend was essential to U.S. security and prosperity in the 21st century.

The claims of both the humanitarian interventionists and the neoconservatives were emotional appeals to different strains in the American psyche, driven and promoted by powerful people and institutions whose careers and interests were bound up in the military industrial complex. The humanitarian interventionists appealed to Americans’ desire to be a force for good in the world. As Madeleine Albright asked Colin Powell, “What’s the point of having this superb military that you’re always talking about if we can’t use it?” On the other hand, the neocons played on the insularity and insecurity of many Americans to insist that the world must be dominated by U.S. military power if we are to preserve our way of life.

The Clinton administration wove many of these claims into a blueprint for global U.S. military expansion in its 1997 Quadrennial Defense Review. The QDR threatened the unilateral use of U.S. military force, in clear violation of the UN Charter, to defend “vital” U.S. interests all over the world, including “preventing the emergence of a hostile regional coalition,” and “ensuring uninhibited access to key markets, energy supplies and strategic resources.”

To the extent that they are aware of the huge increase in military spending since 1998, most Americans would connect it with the U.S. wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and the ill-defined “war on terror.” But Carl Conetta’s research established that, between 1998 and 2010, only 20% of U.S. military procurement and RDT&E (research, development, testing & evaluation) spending and only half the total increase in military spending was related to ongoing military operations. In his 2010 paper, An Undisciplined Defense, Conetta found that our government had spent an extra 1.15 trillion dollars above and beyond Clinton’s FY1998 baseline on expenses that were unrelated to to its current wars.

Most of the additional funds, $640 billion, were spent on new weapons and equipment (Procurement + RDT&E in the Green Book). Incredibly, this was more than double the $290 billion the military spent on new weapons and equipment for the wars it was actually fighting. And the lion’s share was not for the Army, but for the Air Force and Navy.

There has been political opposition to the F-35 warplane, which activists have dubbed “the plane that ate the budget” and whose eventual cost has been estimated at $1.5 trillion for 2,400 planes. But the Navy’s procurement and RDT&E budgets rival the Air Force’s.

Former General Dynamics CEO Lester Crown’s political patronage of a young politician named Barack Obama, whom he first met in 1989 at the Chicago law firm where Obama was an intern, has worked out very well for the family firm. Since Obama won the presidency, with Lester’s son James and daughter-in-law Paula as his Illinois fundraising chairs and 4th largest bundlers nationwide, General Dynamics stock price has gained 170% and its latest annual report hailed 2014 as its most profitable year ever, despite an overall 30% reduction in Pentagon procurement and RDT&E spending since FY2009.

Although General Dynamics is selling fewer Abrams tanks and armored vehicles since the U.S. withdrew most of its occupation forces from Iraq and Afghanistan, its Marine Systems division is doing better than ever. The Navy increased its purchases of Virginia class submarines from one to two per year in 2012 at $2 billion each. It is buying one new Arleigh Burke class destroyer per year through 2022 at $1.8 billion apiece (Obama reinstated that program as part of his missile defense plan), and the FY2010 budget handed General Dynamics a contract to build 3 new Zumwalt class destroyers for $3.2 billion each, on top of $10 billion already spent on research and development. That was despite a U.S. Navy spokesman calling the Zumwalt “a ship you don’t need,” as it will be especially vulnerable to new anti-ship missiles developed by potential enemies. General Dynamics is also one of the largest U.S. producers of bombs and ammunition, so it is profiting handsomely from the U.S. bombing campaign in Iraq and Syria.

Carl Conetta explains the U.S.’s unilateral arms build-up as the result of a lack of discipline and a failure of military planners to make difficult choices about the kind of wars they are preparing to fight or the forces and weapons they might need. But this massive national investment is justified in the minds of U.S. officials by what they can use these forces to do. By building the most expensive and destructive war machine ever, designing it to be able to threaten or attack just about anybody anywhere, and justifying its existence with a combination of neocon and humanitarian interventionist ideology, U.S. officials have fostered dangerous illusions about the very nature of military force. As historian Gabriel Kolko warned in 1994, “options and decisions that are intrinsically dangerous and irrational become not merely plausible but the only form of reasoning about war and diplomacy that is possible in official circles.”

The use of military force is essentially destructive. Weapons of war are designed to hurt people and break things. All nations claim to build and buy them only to defend themselves and their people against the aggression of others. The notion that the use of military force can ever be a force for good may, at best, apply to a few very rare, exceptional situations where a limited but decisive use of force has put an end to an existing conflict and led to a restoration of peace. The more usual result of the use or escalation of force is to cause greater death and destruction, to fuel resistance and to cause more widespread instability. This is what has happened wherever the U.S. has used force since 2001, including in its proxy and covert operations in Syria and Ukraine.

We seem to be coming full circle, to once again recognize the dangers of militarism and the wisdom of the U.S. leaders and diplomats who played instrumental roles in crafting the UN Charter, the Geneva Conventions, the Kellogg Briand Pact and much of the existing framework of international law. These treaties and conventions were based on the lived experience of our grandparents that a world where war was permitted was no longer sustainable. So they were dedicated, to the greatest extent possible, to prohibiting and eliminating war and to protecting people everywhere from the horror of war as a basic human right.

As President Carter said in his Nobel lecture in 2002, “War may sometimes be a necessary evil. But no matter how necessary, it is always an evil, never a good.” Recent U.S. policy has been a tragic experiment in renormalizing the evil of war. This experiment has failed abysmally, but there remains much work to do to restore peace, to repair the damage, and to recommit the United States to the rule of law.

If we compare U.S. military spending with global military spending, we can see that, as the U.S. cut its military budget by a third between 1985 and 1998, the rest of the world followed suit and global military budgets also fell by a third between 1988 and 1998. But as the US spent trillions of dollars on weapons and war after 2000, boosting its share of global military spending from 38% to 48% by 2008, both allies and potential enemies again responded in kind. The 92% rise in the U.S. military budget by 2008 led to a 65% rise in global military spending by 2011.

U.S. propaganda presents U.S. aggression and military expansion as a force for security and stability. In reality, it is U.S. militarism that has been driving global militarism, and U.S.-led wars and covert interventions that have spawned subsidiary conflicts and deprived millions of people of security and stability in country after country. But just as diplomacy and peacemaking between the U.S. and U.S.S.R. led to a 33% fall in global military spending in the 1990s, a new U.S. commitment to peace and disarmament today would likewise set the whole world on a more peaceful course.

In his diplomacy with Cuba and Iran and his apparent readiness to finally respond to Russian diplomacy on Syria and Ukraine, President Obama appears to have learned some important lessons from the violence and chaos that he and President Bush have unleashed on the world. The most generous patron the military industrial complex has ever known may finally be looking for diplomatic solutions to the crises caused by his policies.

But Obama’s awakening, if that is what it turns out to be, has come tragically late in his presidency, for millions of victims of U.S. war crimes and for the future of our country and the world. Whoever we elect as our next President must therefore be ready on day one to start dismantling this infernal war machine and building a “permanent structure of peace”, on a firm foundation of humanity, diplomacy and a renewed U.S. commitment to the rule of international law.

Nicolas J. S. Davies is the author of “Blood On Our Hands: The American Invasion and Destruction of Iraq.” Davies also wrote the chapter on “Obama At War” for the book, “Grading the 44th President: A Report Card on Barack Obama’s First Term as a Progressive Leader.”

Pingback: The record U.S. military budget