I Remember My Name—Poetry by Samah Sabawi, Ramzy Baroud and Jehan Bseiso. Vacy Vlazna, ed., 2016, Novum Publishing. Kindle Edition.

In penning this review, the primacy of Israel in North America’s hegemonic cultural circles limits my expectation of a sympathetic Western readership. The recent furor in Israeli government circles over the public broadcasting of Mahmoud Darwish’s poem is only a warning signal. Thugs and war criminals take on the mantel of literary critics to attack Palestine’s national poet and ascribe to him their own internalized fascist values. Judging from experience the malicious smear is bound to gain traction in Zionist-aligned literary circles at home and abroad. Our lead Palestinian politician in Israel, Ayman Odeh, explains well the Israeli officials’ fear: “If we were to know and acknowledge each other’s culture we may finally want to live together,” [al-Ittihad, July 21, 2016.]

In penning this review, the primacy of Israel in North America’s hegemonic cultural circles limits my expectation of a sympathetic Western readership. The recent furor in Israeli government circles over the public broadcasting of Mahmoud Darwish’s poem is only a warning signal. Thugs and war criminals take on the mantel of literary critics to attack Palestine’s national poet and ascribe to him their own internalized fascist values. Judging from experience the malicious smear is bound to gain traction in Zionist-aligned literary circles at home and abroad. Our lead Palestinian politician in Israel, Ayman Odeh, explains well the Israeli officials’ fear: “If we were to know and acknowledge each other’s culture we may finally want to live together,” [al-Ittihad, July 21, 2016.]

I am an Israeli citizen and know firsthand how Israel’s rightist leaders view the world. I know precisely where my place is in their narrow field of vision. I experience daily how they deal with my issues of the heart; such issues always fall outside the purview of the Israeli majority’s definition of itself. Their politically inspired national, religious and racial exclusionism debases what I and other outfielders say. I live that reality and it strains my ability to reach out to the world, to humanity as a whole. It threatens my poetic and intellectual freedom. I worry that the pro-Israel hegemonic sway in Western culture will affect a ‘security wall’ around my intellectual property and that of other Palestinian writers and of kindred marginalized groups. That, in turn, dims my hope to be understood by the world at large and hence my worry.

The dedication of the current thin collection of poetry by the three internationally savvy poets, Samah Sabawi, Ramzy Baroud and Jehan Bseiso, to Gaza and Gazans blows their cover: They are diaspora Palestinians, world citizens and enemies of hegemonic cultural Zionism from within its field of operation; they are Trojan horses. Between them they span the globe in poetic exile seeming to be in constant flight from the inescapable curse of who they are, Palestinians by nature and nurture.

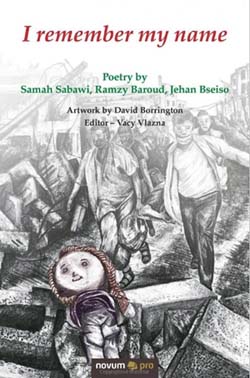

The book is by four poets, not three, for I cried just as much peering into the illustrations as I did reading the lines that inspired them. The way David Borrington renders the feelings behind the words of the poets in heartfelt visual images is a form of poetry as well. How else can he show you again and again what it means to be “anxious at the cellular level” for example?

Samah Sabawi admits to using her “140 characters to liberate Palestine.” Within Israel lesser thought crimes led to a pre-dawn police raid and landed the poet Dareen Tatour first in jail and later in exile from home. The state has deemed her too much a threat to have access to the Internet, or to be free on her own recognizance till the formal court proceedings. But Samah Sabawi, Ramzy Baroud and Jehan Bseiso all have escaped the geographic confines of Palestine/Israel to their emotional and physical global exile. Tethered by their heartstrings to their shared homeland and Gazan suffering, all three transcend their Palestinian roots to a universal core that snares readers everywhere. They soar across the globe to share in the pain of others whether in Kashmir, South Africa, Chile, Burma or Mali.

Between the three of them our poets cover a wide span of the literary field and the physical globe: There isn’t a continent or a writing art they haven’t visited. Whether they cut their sentiments in stone or siphon them from an ocean, the classic similes for the craft of Arabic poetry, all three share the common demeanor coloring the lives of Palestinians everywhere: They harbor a sense of injured pride at the deferred and devalued, even if no longer totally denied, innate justice of their case, the Palestinian Nakba. The hue each of them reflects of this shared, heartfelt and pervasive Palestinian sentiment sets them apart from each other. The editor tells us:

“Although Samah, Ramzy and Jehan have distinctive styles, they possess in common incisive intellects, finely tuned by a sense of justice inherent in the Palestinian experience and in their love for Palestine particularly besieged and suffering Gaza.”

All three poets harbor a deep sense of history, of time and place that always translates to Palestine. I have travelled and met many fellow Palestinians in their diaspora. The phenomenon of Nakba-centered existence is near universal among us. Like a hereditary trait it spans generations and transcends time and space, it colors a Palestinian’s existence wherever he/she treads and whatever air he/she breathes. Take Samah for example: She smiles at us brightly from the first page of her contribution. There is no mistaking her striking Greek (or is it Spanish, Italian, Mexican, Native American or South-East Asian) looks. Speaking for her fellow Palestinian poets, her words live up to the global sentiment her looks spark:

“I am a Palestinian-Canadian-Australian writer, commentator and playwright. . . . I travelled the world and lived in its far corners, yet always felt haunted by the violence and injustice perpetrated against the poor, the marginalized, the colonized and stateless. No matter where I was, or how vast the world appeared around me, I always felt as though I remained trapped in my place of birth Gaza. The war torn besieged and isolated strip shaped my understanding of my identity and my humanity.”

Ramzy concurs:

“Wherever I am in the world, from Seattle to Chile to South Africa and regardless of which struggle I am involved in, from Mali to the Rohingya, I am always thinking Palestine, even when I am not conscious of it.

“So, don’t talk to me about the Pharaoh:

My Father’s blood drenched the skin of Jesus

After the Romans caught him at a checkpoint

Hiding a recipe for revolution, and a love poem”

And here is Jehan Bseiso:

“Since 2008 I have been working with Médecins Sans Frontières—Doctors Without Borders. My work has taken me to countries like Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Ethiopia and others. In all my travels and encounters, I’ve experienced how support and understanding of the Palestinian cause can cross borders and traverse barriers of culture and language.”

The with-it modernity of the three exiled Palestinian poets is such that it makes it possible to include such scribbles as “@ CNN@ Foxnews” meaningfully in a poem. Yet on the first reading, it is only at the very end that the picture becomes stunningly clear, explained in a single exclamation “Hashtag Gaza.” This gives the entire collection its full clarity: Samah floats on an ethereal atmosphere focusing on Gaza willingly or against her will, Ramzy fills every internationally significant calamity with his remembered Gazan content and Jehan experiences everything firsthand as #Gaza.

“How [else] can we remember what we can’t forget?”

Aversion to hyperbole limits one’s choices for comparison. Still, Gaza’s reality is of the same genre as the Holocaust or Hiroshima. Except that Gaza’s plight is stretched out over decades with the perpetrators’ skilled consistency and aggressive projection of inner violence on its victim so artfully that violence becomes the norm for Gaza if not for the whole of Palestine. The ‘international community’ is numbed into accepting the buzz of its drones, helicopters and F-16s as part of the standard background noise and its fireworks as another light show to observe and to report on occasionally to fill the bulk requirements of international dailies.

“Counting lashes is unlike receiving them,” a Palestinian saying goes. The Palestinian experience, especially in Gaza, not only of suffering but also of being ignored, shunned and ridiculed for incurring such punishment is extremely private. It is so private and foreign it is difficult to communicate to others. The basic elements of their private world are so harshly incomprehensible that even when you scream them at ‘normal people’ you do it out of despair knowing that such reality is unexplainable, that only living such reality permits one to understand it.

Hence, and logically, some of the language is so unusual as poetry that it rubs against the grain. And yet, there is an amateurish freshness to the raw rub and the sanguinity of it all. It is so painfully touching it sinks and sticks to the depth of the heart:

“Habeebi, I thought you lost my number, turns out you lost your legs.”

How else can one perceive such nightmarish reality as:

“In the hospital, they put the pregnant women alone, because they’re carrying hope, because they don’t want them to see what can happen to children.

. . . There’s more blood than water today in Gaza.”

Dr. Hatim Kanaaneh is the author of “Chief Complaint” as well as “A Doctor in Galilee: The Life and Struggle of a Palestinian in Israel” (Pluto Press, 2008).