“Ford to New York: Drop Dead,” said a famous headline in 1975. President Ford had declared flatly that he would veto any bill calling for “a federal bail-out of New York City.” What he proposed instead was legislation that would make it easier for the city to go bankrupt.

Now the Federal Treasury and Federal Reserve seem to be saying this to the states, which are slated to be the first ritual victims in the battle over the budget ceiling. On May 2, Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner said that the Treasury would stop issuing special securities that help state and local governments pay for their debt. This was to be the first in a series of “extraordinary measures” taken by the Treasury to avoid default in the event that Congress failed to raise the debt ceiling on May 16. On May 13, the Secretary said these extraordinary measures had been set in motion.

The Federal Reserve, too, has declared that it cannot help the states with their budget problems—although those problems were created by the profligate banks under the Fed’s purview. The Fed advanced $12.3 trillion in liquidity and short-term loans to bail out the financial sector from the 2008 banking collapse, 64 times the $191 billion required to balance the budgets of all 50 states. But Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke declared in January that the Fed could not make the same cheap credit lines available to state and local governments—not because the Fed couldn’t find the money, but because it was not in the Fed’s legislative mandate.

The federal government can fix its own budget problems by raising its debt ceiling, and the too-big-to-fail banks have the federal government and Federal Reserve to fall back on. But these options are not available to state governments. Like New York City in 1975, many states are teetering on bankruptcy.

A beacon in the storm

Many states are in trouble, but not all. North Dakota has consistently boasted large surpluses, aided by a state-owned bank that is showing landmark profits. On April 20, the Bank of North Dakota (BND) reported profits for 2010 of $62 million, setting a record for the seventh straight year. The BND’s profits belong to the citizens and are produced without taxation.

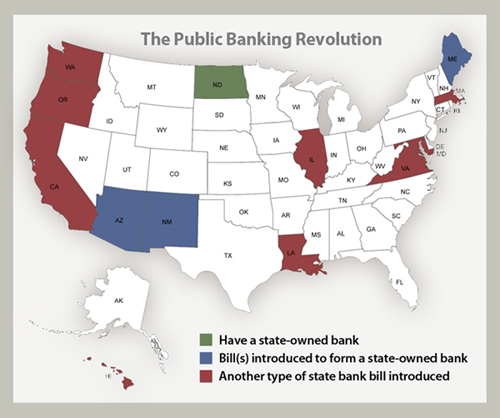

Inspired by North Dakota’s example, twelve states have now introduced bills to form state-owned banks or to study their feasibility. Eight of these bills have been introduced just since January, including in Oregon, Washington State, Massachusetts, Arizona, Maryland, New Mexico, Maine and California. Illinois, Virginia, Hawaii and Louisiana introduced similar bills in 2010. For links, dates and text, see here.

The Center for State Innovation, based in Madison, Wisconsin, was commissioned to do detailed analyses for Washington and Oregon. Their conclusion was that a state-owned bank on the model of the Bank of North Dakota would have a substantial positive impact on employment, new lending, and government revenue in those states.

The BND partners with local banks in providing much-needed credit for local businesses and homeowners. It also helps with local government funding needs. When North Dakota went over-budget a few years ago, according to the bank’s president Eric Hardmeyer, the BND acted as a rainy day fund for the state; and when a North Dakota town suffered a massive flood, the BND provided emergency credit lines to the city. Having a cheap and readily available credit line with the state’s own bank reduces the need for massive rainy-day funds that are a waste of capital and are largely invested in out-of-state banks at very modest interest.

What states can do with their own banks

North Dakota has a population that is less than 1/10th the size of Los Angeles. The BND produced $62 million in revenue last year and $2.2 billion in loans. Larger states could generate much more.

Banks create “bank credit” from capital and deposits, as explained here. The Bank of North Dakota has $2.7 billion in deposits, or $4000 per capita. The majority of these deposits are drawn from the state’s own revenues. The bank has nearly the same sum ($2.6 billion) in outstanding loans.

You can get a rough idea of what a state bank could do for your state, then, by multiplying the population by $4,000. California, for example, has 37 million people. If it had a state-owned bank that performed like the BND, it might amass $148 billion in deposits. This $148 billion could then generate $142 billion in credit for the state, assuming the bank could come up with $12 billion in capital to satisfy the 8% capital requirement imposed on banks.

Note that this capital would not be an expenditure. It would just be an investment; and like any capital investment, it would actually make money for the state. The Bank of North Dakota has had a return on equity in recent years of 25–26%, and a major portion of this has been returned to the state treasury. All states have massive rainy day funds of various sorts. Some of this money could simply be shifted into equity in the state’s own bank.

There are many options for using the state’s credit power, but here is one easy alternative that illustrates the cost-effectiveness of the approach. Assume California’s state-owned bank invested $142 billion in municipal bonds at 5% interest. This would give the state $7 billion annually in interest income. California has outstanding general obligation bonds and revenue bonds of $158 billion, and $70 billion goes for interest. If California had been funding its debt through its own bank for the last decade or two, it would have saved $70 billion on its bonded debt and would be that much richer today.

In a futile attempt to “balance the budget” in a shrinking economy, we have been pressured into a self-destructive economic model in which the only alternatives are said to be to slash services, raise taxes, and sell off public assets. These are not our only alternatives. What destroyed our local economies was not excess government spending but was a credit crisis on Wall Street. We can restore the prosperity we lost by restoring credit in the state; and we can do that by taking our deposits out of Wall Street banks and putting them in our own state-owned bank, to be leveraged into credit for local purposes. For more information, see here.

Ellen Brown is an attorney and president of the Public Banking Institute, http://PublicBankingInstitute.org. In Web of Debt, her latest of eleven books, she shows how a private cartel has usurped the power to create money from the people themselves, and how we the people can get it back. Her websites are http://webofdebt.com and http://ellenbrown.com.

I had to refresh the page times to view this page for some reason, however, the information here was worth the wait.