North Korea was not the first power on the Korean peninsula to pursue the acquisition of nuclear weapons. That distinction goes to U.S. ally South Korea under the dictatorship of Park Chung Hee. Ironically, as the U.S. corporate media joins the Pentagon in rattling war sabers against North Korea, the daughter of the South Korean leader who gave the green light to a South Korean nuclear arsenal, Park Geun-hye, was recently placed in prison on criminal fraud charges following her impeachment and removal from the South Korean presidency.

Currently, U.S. news networks are sending crews to South Korea to file reports on the U.S. military readiness to repel an attack from the North. Along with those reports come advertisements from such war contractors as Northrop Grumman, Boeing, and Lockheed Martin.

A Confidential cable from the U.S. embassy in Seoul to Secretary of State Henry Kissinger on July 30, 1974, just a little over a week before the resignation of President Richard Nixon, set off quiet alarms in Washington. A South Korean official told the U.S. ambassador in Seoul that word reached Seoul that North Korea was preparing to ratify the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). While such a move would have been welcomed in the region as a step toward de-nuclearization of the Korean peninsula, the South Korean government waffled on whether it would follow Pyongyang’s lead in acceding to the NPT.

In fact, as a series of U.S. State Department cables indicate, the South Koreans had no intention of following Pyongyang on ratifying the NPT. The reason was simple: the Park dictatorship had secretly been developing its own nuclear arsenal.

Seoul began letting its nuclear cat out of the bag in an editorial in the July 12, 1974, edition of the Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA)-dominated newspaper Kyunghyang Shinmun. The editorial thought it unwise for South Korea to pursue non-proliferation under the American nuclear protection umbrella. The cable from Seoul to Kissinger stated that the editorial was unambiguous about Seoul’s intentions: “the ROK [Republic of Korea] can no longer take a negative attitude on the spread of nuclear capability out of humanitarian or sentimental concerns.” The cable contained a stark warning for Washington: “Most senior ROK defense planners desire to obtain capability eventually to produce nuclear weapons.” The cable added that U.S. pressure on Seoul could be expected to be met by “growing independence” by South Korea on defense matters.

The year 1974 presented a “perfect storm” for South Korea to embark on a nuclear weapons program. The skyrocketing of oil prices that year propelled South Korea’s nuclear power industry, which was bolstered by two Westinghouse nuclear power plants then under construction and contracts for Canada to supply South Korea with two CANDU reactors. In addition, Seoul was talking to Gulf General Atomics about obtaining three 800-megawatt reactors that used highly-enriched uranium fuel. Moreover, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), believing South Korea to be “loyal” to the cause of nuclear non-proliferation, heartily endorsed the South’s obtaining additional nuclear power plants through 1985.

The highly-enriched uranium obtained by the South was also necessary for the development of nuclear weapons. South Korea also had a separate covert program to develop weapons-grade plutonium. As seen from its acquisition of “dual use” nuclear technology, Seoul’s nuclear weapons program had gone far beyond the planning stages when the U.S. embassy in Seoul first alerted Kissinger about Seoul’s nuclear ambitions.

The Canadian ambassador in Seoul informed his U.S. counterpart that Canada was aware that South Korea might decide to divert its CANDU nuclear reactor technology to nuclear weapons production. In August 1974, Park, obviously aware that Washington was preoccupied with the resignation of Nixon and was not looking closely at Korea, privately told South Korean journalists that he ordered South Korean scientists to develop atom bombs by 1977. The CIA then believed that South Korea could develop its own nuclear bomb by 1980 by diverting technology for its nuclear power plants and secretly acquiring nuclear fuel reprocessing equipment from France. Park’s agents also approached McDonnell-Douglas to acquire 200-mile range ballistic missiles capable of reaching Pyongyang from South Korean territory.

Under tremendous pressure from the Gerald Ford administration, South Korea, which had signed the NPT in 1968, finally ratified it in 1975. However, it is believed that work never actually stopped on South Korea’s nuclear weapons program. Like that of Japan, it was buried deep within the “peaceful” nuclear power program. During the Jimmy Carter administration, when it was announced that the U.S. would withdraw its ground troops from South Korea, Park resumed the covert South Korean nuclear weapons program by secretly trying to obtain nuclear fuel reprocessing technology and materials from France. South Korea was not the only country with nuclear weapons aspirations to have approached the French for reprocessing capabilities. The French were negotiating a similar agreement with Pakistan.

It was South Korea’s pursuit of nuclear weapons that resulted in North Korea pressuring China and the Soviet Union for a similar capability. Pyongyang’s intention of ratifying the NPT was a casualty of Seoul’s intentions. There is no evidence that either Beijing or Moscow provided the North with nuclear weapons technology, decisions that prompted the North to look elsewhere.

In 1992, after the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, North and South Korea signed the “Joint Declaration of South and North Korea on the Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.” Although the North had not signed the NPT, it agreed with Seoul to not seek to “possess nuclear reprocessing and uranium enrichment facilities.” Furthermore, North and South vowed that they would not “test, manufacture, produce, receive, possess, store, deploy or use nuclear weapons.” North Korea proceeded to violate the North-South accord by continuing to develop a nuclear weapons capability. It tested an underground nuclear weapon at the Punggye-ri Test Site in 2006.

In 2004, the South Koreans had a surprise for the IAEA. It declared to the agency that it had conducted uranium enrichment and conversion and plutonium separation experiments at the Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute (KAERI). The IAEA considered the South’s breach a severe violation of the NPT. The South Korean government said the experiments had been conducted “without the knowledge or authorization of the government.” In a structured society like South Korea, the claim by Seoul was laughable, if it had not been so serious a move to acquire weapons-grade nuclear material.

It takes a certain amount of tact, patience, and experience to deal with North Korea: Jimmy Carter with Kim Il Sung, 1994, left, Secretary of State Madeleine Albright and Kim Jong Il, 2000 center, Bill Clinton with Kim Jong Il, 2009 right. Trump misses out on all three requirements.

Today, the war mongers inside the Trump administration are hankering for a military showdown with North Korea. Such brinkmanship comes at a potential deadly cost to the United States. There are over 130,000 American citizens, including military forces, living in South Korea. Most live within range of North Korean artillery, which, in the first stages of a military conflict, will rain down their shells on metropolitan Seoul.

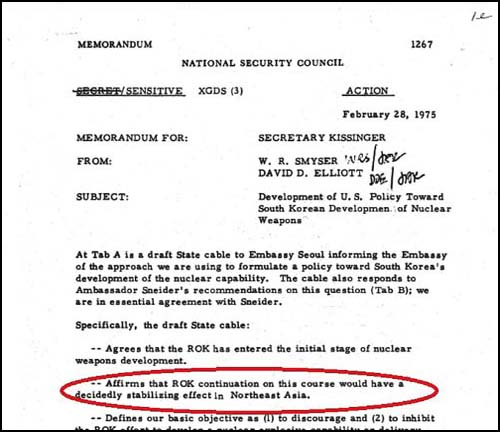

The Trump administration appears to be as befuddled and incompetent on Korea as was the Ford administration. For example, a February 28, 1975, National Security Council memo to Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, who also served as National Security Adviser, stated that South Korea’s “initial stage of nuclear weapons development . . . would have a decidedly stabilizing effect in Northeast Asia,” when the exact opposite was the case.

South Korea’s covert nuclear weapons program under Park came to a halt in 1979 after the South Korean president was shot to death by his own KCIA chief. Although the KCIA’s founding organization, the U.S. CIA, denied any role in the assassination, it was noted that the normal CIA complement of between 40 and 50 agents at the CIA station in Seoul doubled to over a 100 just prior to the assassination. Most of the agents worked out of the U.S. embassy’s 5th floor, in what was called the CIA’s “Research Unit.”

North Korea’s leader, Kim Jong Un, is an unstable character. However, he was schooled in Switzerland and is the first in three generations of Kim leaders to have lived in a Western country, becoming familiar with Western “culture,” good and bad. Kim’s grandfather Kim Il Sung and father Kim Jong Il were experienced Communist Party functionaries and were capable of diplomacy while not always abiding by international agreements. Kim Il Sung met in Pyongyang in 1994 with former President Jimmy Carter. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright met with Kim Jong Il in 2000 in Pyongyang, a meeting that was followed by one between Kim Jong Il and former President Bill Clinton in 2009. Kim Il Jong’s sudden death in 2011, which may not have been by natural causes, ended high-level contacts between Pyongyang and Washington.

Kim Jong Un is a loose cannon, as seen with his ordering the assassination by VX nerve agent of his half-brother, Kim Jong-nam, at Kuala Lumpur International Airport. However, even a loose cannon can be lured with the dangling of lucrative “carrots.” However, the Trump administration and its neanderthal thinkers like CIA director Mike Pompeo lack the gravitas to come up with a unique way to deal with Kim Jong Un without setting the Korean peninsula ablaze with a nuclear fire.

One thing is for certain. Neither China nor Russia will permit the U.S. Pacific Command to extend its territory to the Yalu River border with China or the Tumen River border with Russia. Unlike West Germany’s unification with East Germany, there is no great desire among most South Koreans to absorb North Korea. An exception is the very elderly who still have relatives in the North. Therefore, any move to eliminate Kim from the scene will only have the support of China and Russia if a new North Korean regime adheres to a strict neutrality, guaranteed by all the powers in the region, including Japan and the United States.

There is likely an anti-Kim faction within the North Korean military that would move against the Kims if they were guaranteed leadership of a neutral North Korea in return for abandoning the North’s nuclear weapons program. The best the U.S. can hope for is the emergence of a North Korean version of Marshal Tito, someone that will keep his country stable as a strictly neutral power in exchange for a guarantee of non-aggression from all regional powers, including the United States and a rapidly re-militarizing Japan. However, the North will need an insurance policy and that is its continued possession of short- and intermediate-range conventional missiles, not the intercontinental ballistic missiles like the one just test-fired by North Korea.

Trump considers himself the ultimate deal maker. However, given the presence of James Mattis at the Pentagon, Pompeo at the CIA, and right-wing lunatic Stephen Bannon always at Trump’s side, Trump will not be able to deal with Pyongyang because he frankly lacks the intelligence and education to carry off such a feat. While “only Nixon could go to China,” Trump does not have the wherewithal to navigate his way back to New York on the New Jersey Turnpike. On the issue of North Korea, a Trump White House official was anonymously quoted as saying, “The clock has now run out [on North Korea], and all options are on the table.” That is not incredibly original or insightful.

Previously published in the Wayne Madsen Report.

Copyright © 2017 WayneMadenReport.com

Wayne Madsen is a Washington, DC-based investigative journalist and nationally-distributed columnist. He is the editor and publisher of the Wayne Madsen Report (subscription required).