Illinois is insolvent, unable to pay its bills. According to Moody’s, the state has $15 billion in unpaid bills and $251 billion in unfunded liabilities. Of these, $119 billion are tied to shortfalls in the state’s pension program. On July 6, 2017, for the first time in two years, the state finally passed a budget, after lawmakers overrode the governor’s veto on raising taxes. But they used massive tax hikes to do it—a 32% increase in state income taxes and 33% increase in state corporate taxes—and still Illinois’ new budget generates only $5 billion, not nearly enough to cover its $15 billion deficit.

Adding to its budget woes, the state is being considered by Moody’s for a credit downgrade, which means its borrowing costs could shoot up. Several other states are in nearly as bad shape, with Kentucky, New Jersey, Arizona and Connecticut topping the list. U.S. public pensions are underfunded by at least $1.8 trillion and probably more, according to expert estimates. They are paying out more than they are taking in, and they are falling short on their projected returns. Most funds aim for about a 7.5% return, but they barely made 1.5% last year.

If Illinois were a corporation, it could declare bankruptcy; but states are constitutionally forbidden to take that route. The state could follow the lead of Detroit and cut its public pension funds, but Illinois has a constitutional provision forbidding that as well. It could follow Detroit in privatizing public utilities (notably water), but that would drive consumer utility prices through the roof. And taxes have been raised about as far as the legislature can be pushed to go.

The state cannot meet its budget because the tax base has shrunk. The economy has shrunk and so has the money supply, triggered by the 2008 banking crisis. Jobs were lost, homes were foreclosed on, and businesses and people quit borrowing, either because they were “all borrowed up” and could not go further into debt or, in the case of businesses, because they did not have sufficient customer demand to warrant business expansion. And today, virtually the entire circulating money supply is created when banks make loans When loans are paid down and new loans are not taken out, the money supply shrinks. What to do?

Quantitative easing for munis

There is a deep pocket that can fill the hole in the money supply—the Federal Reserve. The Fed had no problem finding the money to bail out the profligate Wall Street banks following the banking crisis, with short-term loans totaling $26 trillion. It also freed up the banks’ balance sheets by buying $1.7 trillion in mortgage-backed securities with its “quantitative easing” tool. The Fed could do something similar for the local governments that were victims of the crisis. One of its dual mandates is to maintain full employment, and we are nowhere near that now, despite some biased figures that omit those who have dropped out of the workforce or have had to take low-paying or part-time jobs.

The case for a “QE-Muni” was made in an October 2012 editorial in The New York Times titled “Getting More Bang for the Fed’s Buck” by Joseph Grundfest et al. The authors said Republicans and Democrats alike have been decrying the failure to stimulate the economy through needed infrastructure improvements, but shrinking tax revenues and limited debt service capacity have tied the hands of state and local governments. They observed:

State and municipal bonds help finance new infrastructure projects like roads and bridges, as well as pay for some government salaries and services.

. . . [E]very Fed dollar spent in the muni market would absorb a larger percentage of outstanding debt and is likely to have a greater effect on reducing the bonds’ interest rates than the same expenditure in the mortgage market.

. . . [L]owering the borrowing costs for states, cities and counties should not only forestall tax increases (which dampen individual spending), but also make it easier for local governments to pay for police officers, firefighters, teachers and infrastructure improvements.

The authors acknowledged that their QE-Muni proposal faced legal hurdles. The Federal Reserve Act prohibits the central bank from purchasing municipal government debt with a maturity of more than six months, and the beneficial effects expected from QE-Muni would require loans of longer duration. But Congress was then trying to avoid the “fiscal cliff,” so all options were on the table. Today the fiscal cliff has come around again, with threats of the debt ceiling dropping on an embattled Congress. It could be time to look at “QE for Munis” again.

Getting more bang for the pensioners’ bucks

Scott Baker, a senior advisor to the Public Banking Institute and economics editor at OpEdNews, has another idea. He argues that the states are far from broke. They may not be able to balance their budgets with taxes, but a search through their Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports (CAFRs) shows that they have massive surplus funds and rainy day funds tucked away around the state, most of them earning minimal returns. (Recall the 1.5% made by the pension funds collectively last year.)

The 2016 CAFR for Illinois shows $94.6 billion in its pension fund alone, and well over $100 billion if other funds are included. To say it is broke is like saying a retired couple with a million dollars in savings is broke because they can earn only 1.5% on their savings and cannot live on $15,000 a year. What they need to do is to spend some of their savings to meet their budget and invest the rest in something safe but more lucrative.

So here is Baker’s idea for Illinois:

- Make an iron-clad pledge by law, even in the State Constitution if they can get quick agreement, to provide for pension payouts at the current level and adjusted for inflation in the future.

- Liquidate the current pension fund and maybe some of the other liquid funds too to pay off all current debts.

- This will leave them with a great credit rating. . . .

- Put the remaining tens of billions into a new State Bank, partnering with the beleaguered small and community banks. . . . Use that money to finance state and local businesses and individuals instead of Wall Street schemes and high fund manager fees that will no longer be necessary or advisable, saving the state hundreds of millions a year.

The Public Bank could be built roughly on the model of the hugely successful Bank of North Dakota example, one of the country’s greatest banks, measured by Return on Equity, and scandal-free since its founding in 1919.

The Bank of North Dakota (BND), the nation’s only state-owned bank, has had record profits every year for the last 13 years, with a return on equity in 2016 of 16.6%, twice the national average. Its chief depositor is the state itself, and its mandate is to support the local economy, partnering rather than competing with local banks. Its commercial loans range from 2.4% to 7.5%. The BND makes cheaper loans as well, drawing on loan funds for special programs including infrastructure, startup businesses and affordable housing. Its loan income after deducting allowances for loan losses was $175 million in 2016 on a loan portfolio of $4.7 billion. (2016 BND CAFR, pages 28–29.)That puts the net return on loans at 3.7%.

Illinois could follow North Dakota’s lead. Looking again at the Illinois CAFR (page 45), the amount paid out for pension benefits in 2016 was only $1.833 billion, or less than 2% of the $94.6 billion pool. An Illinois state bank could generate that much in profit, even after paying off the state’s outstanding budget deficit.

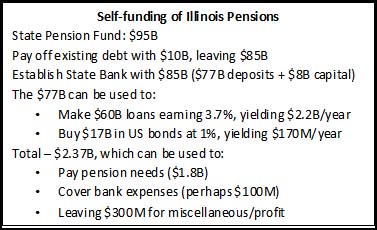

Assume Illinois guaranteed its pension payouts, as Baker recommends, then liquidated its pension fund and withdrew $10 billion to meet its current budget shortfall. This would significantly improve its credit rating, allowing it to refinance its long-term debt at a reduced rate. The remaining $85 billion could be put into the state’s own bank, $8 billion as capital and $77 billion as deposits. [See chart below.] At a loan to deposit ratio of 80%, $60 billion could be issued in loans. At a return similar to the BND’s 3.7%, these loans would produce $2.2 billion in interest income. The remaining $17 billion in deposits could be invested in liquid federal securities at 1%, generating an additional $170 million. That would give a net profit of $2.37 billion, enough to cover the $1.8 billion annual pensioners’ payout, with $570 million to spare.

The salubrious result: the pension fund would be self-funding; the state would have a bank that could create credit to support the local economy; the pensioners would have money to spend, increasing demand; the economy would be stimulated, increasing the tax base; and the state would have a good credit rating, allowing it to borrow on the bond market at low interest rates. Better yet, it could borrow from its own bank and pay the interest to itself. The proceeds could then go to its pensioners rather than to bondholders.

Where there is the political will, there is a way. Politicians and central bankers will take radical, game-changing steps in desperate times. We just need to start thinking outside the box, a Wall Street-imposed box that has trapped us in austerity and economic servitude for over a century.

Ellen Brown is an attorney, founder of the Public Banking Institute, a Senior Fellow of the Democracy Collaborative, and author of twelve books including Web of Debt and The Public Bank Solution. A 13th book titled The Coming Revolution in Banking is due out this fall. She also co-hosts a radio program on PRN.FM called “It’s Our Money.” Her 300+ blog articles are posted at EllenBrown.com.