Author’s Note: This is Part Two in a multi-part series direct and on-scene from the Mid-East. For background info. not repeated here, please see Part One.

“We have seen war . . . too much war. We desire peace. To have peace we must live together as one people. The new government says so. We support our government.”—Taxi driver on the streets of Beirut.

Indeed the people of Lebanon have seen too much war. Though their military has not in its history set foot on foreign soil, remaining in the minds of the Lebanese are one bloody civil war and three separate wars of invasion in 1982, 1999, and 2006. Now it would appear that a new war is brewing again on its southern border.

In all these examples war was brought to their land by Israel who, using false premise, attacked the civilian population and infrastructure at will, attempting and failing to conquer the capital city, Beirut. Despite this history, all Lebanese—except the Palestinian refugee population—desire peace with Israel, but they too well understand the need for a well prepared army. An army of the people and for the people.

As Mao observed in his book, Guerrilla Warfare, “In order to put down the gun, one must first pick-up the gun.” This, applied to continued Israeli military foreign policy that continues to threaten them, is the sad, reluctant reality that faces this peaceful country at this very moment. However, considering the examples of military force in Turkey, documented in a previous article, this army—their army—is very different indeed.

Arriving from Turkey into Beirut-Rafic Hariri International Airport just south of Beirut city, the differences become immediately obvious. The airport’s immigration and customs workers and security guards do their job, but they are not aggressive. A Canadian reporter can easily be mistaken for being American, unfortunately in the minds of some a good reason for a lack of politeness, but here you are treated with courtesy, although sometimes somewhat abruptly, by the staff who all wear military uniforms.

The people here are jovial, smiling and willing to help. They exude a carefree spirit regardless of the prior ravages of war being always at hand. Beirut is known for its very late, night life that goes on seven nights a week, often until 4 AM or later. As one Saturday night reveler summed up, beer in hand and a cigarette waving in the other, “We party like it’s our last night on earth . . . because it might be!”

Many speak English due to three languages being required in Lebanese colleges; Arabic, English and an elective language of a student’s choice. Literacy is high and politics is spoken freely. As such, the traveler feels at home, safe . . . and very welcome. Buying a tall beer at any Beirut bar, a quick introduction to anyone at arm’s length is all that it takes to make new friends. Politics is spoken freely and they desire opinion on what is going on in the West, especially applied to the new American president and his willingness for new war and for providing Israel carte blanche in its expansionist efforts against the Arab nations. Rightfully, they are concerned about the advent of new war.

Sadly, there are far fewer Western and EU travellers bringing much needed tourist money to an increasingly impoverished Lebanon these days. The Syrian war is mere miles away to the east and although standard media reports that it is winding down, two important facts are widely known to the average Lebanese: The Americans and their manufactured minions of war refuse to leave and the Israelis are preparing to invade their country again—for the fifth time—via their southern border. For the moment, most areas here are safe and visitors have very little to fear, but this can again change, as before, at the whim of these two foreign powers.

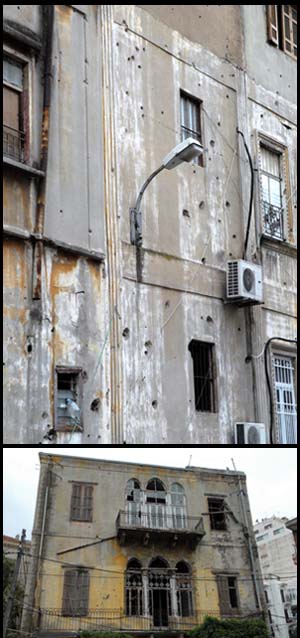

Driving into Beirut many buildings show the pock marks of hundreds of bullets holes still there from the civil war of 1975- 1990 as they strangely sit immediately next to other renovated high-rise apartments. Others sit dormant, dark brownish black streaks staining their exterior walls where fire and smoke once billowed from their now glassless windows after the Israeli bombings of the civilian neighbourhoods in the four previous wars. The worst of these structures are held together by a patch work of interlocked reddish, two inch steel piping secured together to keep these ruins from suddenly falling apart in total. This scene is exactly repeated across the many miles expanse of the suburbs that is today’s Beirut, a city that has been victimized by invasion too often and that is a daily reminder to the Lebanese of the past.

Driving into Beirut many buildings show the pock marks of hundreds of bullets holes still there from the civil war of 1975- 1990 as they strangely sit immediately next to other renovated high-rise apartments. Others sit dormant, dark brownish black streaks staining their exterior walls where fire and smoke once billowed from their now glassless windows after the Israeli bombings of the civilian neighbourhoods in the four previous wars. The worst of these structures are held together by a patch work of interlocked reddish, two inch steel piping secured together to keep these ruins from suddenly falling apart in total. This scene is exactly repeated across the many miles expanse of the suburbs that is today’s Beirut, a city that has been victimized by invasion too often and that is a daily reminder to the Lebanese of the past.

Yes, all Lebanese want peace. The problem is, that peace is not up to them. As seen in Syria, the Western powers care not at all for peace, a nation’s sovereignty, nor human life. These shattered scenes here, in what was once called the “Paris of the Middle East,” provide an ever-present reminder—a warning—of this horrible truth.

“We are not afraid of our military. We welcome them. They make us feel safe. They are here to protect Lebanese . . . to protect Lebanon. This is good.”—Shopkeeper in downtown Beirut.

The streets of Beirut have a very large military presence. Everywhere. Whether it is the police, private security, or soldiers they all wear the same multi-grey-on grey with black and white camouflage uniforms. This creates a very visual presence. At the lowest level a very few, such as parking attendants, are not armed. For the rest one can tell the difference in affiliation by the standard Kalashnikov automatic rifles they hold and then counting the number of extra banana clip bullet magazines strapped to their bodies. Police have only the one clip; in their rifle. The military have six!

Watching one set of police work the scene of a minor traffic accident involving a car and motor scooter, the senior officer is standing across the street next to his white and black SUV while casually smoking a cigarette. He is watching his men closely. Suddenly he moves quickly to the rear of his truck. He has noticed that his men are not properly armed. Snatching-up two AK-47’s, he quickly crosses the street and thrusts the weapons into their grasp, making them well aware of their mistake and his displeasure. He, like the rest of the Lebanese military, are taking no chances, not now . . . not ever!

The cops and the military, however, are pleasant. They watch their areas carefully, but are friendly and readily smile and chat with passers-by, often in front of the backdrop of the bullet riddled buildings, and treat strange reporters the same way despite the language barrier. They are everywhere in Beirut, but do not harass or intimidate. They smoke, chat and seem relaxed while holding their rifles that do not leave their hands . . . but they do not sit. Those with patrol cars are never inside them, instead standing on display, similarly ready for action, as the senior officer at the traffic accident had previously demanded of his own men. There is much to fear in Lebanon, but is not the people. And it is not the police.

The cops and the military, however, are pleasant. They watch their areas carefully, but are friendly and readily smile and chat with passers-by, often in front of the backdrop of the bullet riddled buildings, and treat strange reporters the same way despite the language barrier. They are everywhere in Beirut, but do not harass or intimidate. They smoke, chat and seem relaxed while holding their rifles that do not leave their hands . . . but they do not sit. Those with patrol cars are never inside them, instead standing on display, similarly ready for action, as the senior officer at the traffic accident had previously demanded of his own men. There is much to fear in Lebanon, but is not the people. And it is not the police.

Wandering the streets safely late one night, yet hopelessly lost amongst the myriad of tall apartment buildings that border each side of the street and provide no point of reference at all, two well armed soldiers—special forces by the looks of their ruby-red caps—notice this stranger approaching them and . . . that he has somehow managed to be inside their closed perimeter. They turn, facing the stranger, admonishing him in obvious Arabic that he is definitely in the wrong place. However, they do not draw their weapons, rather they check him out closely, looking with close scrutiny as he gets closer. The stranger’s heart rate is increasing despite what he has observed that day having previously dealt with American cops and military far too often in his travels and fallen victim to their aggressions far too often. Now his thumping heart palpitations throb at his temples as he closes the gap on this dark, silent street . . . a natural reaction due to past experience.

Now within ten feet, the two special forces officers begin to smile, then laugh politely at the foreigners predicament, although pointing adamantly that he should move immediately outside their gate and their security zone. No English is spoken, but they point the way back to a landmark and home, shaking their heads in amusement as the stranger ambles on, finally in the correct direction. This of course is a far cry from how their American counterparts would likely have handled this very innocent situation.

For the remainder of my time in Beirut I never again had any remaining fear at all of this military. A military that shows itself regularly, as on this night, to be . . . an Army for the People.

Author’s Note: This concludes Part Two of a multi-part series. Coming next: “Hezbollah: You don’t see them . . . they see you!”

Brett Redmayne-Titley has published over 150 in-depth articles over the past seven years for news agencies worldwide. Many have been translated. On-scene reporting from important current events has been an emphasis that has led to multi-part exposes on such topics as the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations, NATO summit, KXL Pipeline, Porter Ranch Methane blow-out and many more. He can be reached at: live-on-scene((at)) gmx.com. Prior articles can be viewed at his archive: www.watchingromeburn.uk.