In Hartford, Vermont, last year, U.S. Border Patrol agents boarded a Greyhound bus as it arrived from Boston, asking passengers about their citizenship and checking the IDs of people of color or those with accents. In January, they stopped a man in Indio, California, as he was boarding a Los Angeles-bound bus. In questioning him about his immigration status, they told him his “shoes looked suspicious,” like those of someone who had recently crossed the border.

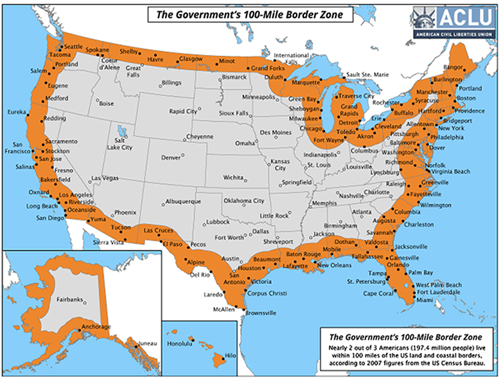

Interrogation, searches, demands for identification and possible detainment are processes people are subjected to as they try to enter the U.S. at ports of entry as the U.S. Customs and Border Protection tries to keep borders secure. Turns out, this broad authority doesn’t end at ports of entry but extends for another 100 miles into the interior, across the entire perimeter of the country.

It’s an area some derisively refer to as the “Constitution-Free Zone.” It’s also home to two-thirds of the U.S. population.

Within this area, U.S Border Patrol, a division of Customs and Border Protection, has authority to board and search any vehicle, bus, or vessel without a warrant and can ask occupants to prove their legal status in this country: “Papers, please.”

Some 200 million people live within that 100-mile zone, which encompasses most major U.S. cities from east to west and north to south, including New York and Seattle, Detroit and Philadelphia. The zone also includes the entirety of many states, Florida, Massachusetts, and New Jersey, for example.

This wide authority, which appears to conflict with constitutional rights, is contained in a statutory change to the Immigration and Nationality Act more than 70 years ago. Regulations later established the 100-mile zone. The ACLU and other constitutional scholars have long argued that the 100-mile zone violates Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable search and seizure, but the U.S. Supreme Court has consistently upheld it.

Within this 100-mile perimeter, the Border Patrol has broad authority to board and search any vehicle without a warrant and ask occupants to prove their legal status.

The warrantless bus raids have mobilized organizations and grassroots efforts to rein them in.

In Florida, a coalition of immigrant advocacy groups in February issued a Travel Advisory warning people to “reconsider traveling to the state because of the increased likelihood of racial profiling and abuse of civil liberties.” One of those groups, the Florida Immigration Coalition, whose members shared videos that went viral of January border patrol raids, has begun an online petition asking Greyhound to stop allowing the agents onto its buses.

The videos of officers removing from a Greyhound bus a Jamaican grandmother who had been visiting her granddaughter and later of a Trinidadian man being led away in handcuffs got nearly 1 billion combined views, said Melissa Taveras, spokeswoman for FLIC, which advocated on behalf of the passengers.

Florida restricts drivers’ licenses for those in the country without legal status, leaving some people few options for getting around.

“Americans deserve to ride the bus in peace without having to carry a birth certificate or passport to travel,” the group says in its petition. “In 2018, it is outrageous that there is an Apartheid-like passbook requirement to travel within your own state.”

This week, ACLU officers in 10 border states sent a joint letter to Greyhound executives urging them to exercise their Fourth Amendment rights and stop the raids.

Law students from the ACLU-affiliated Gonzaga University Center for Civil and Human Rights were handing out “Know your Rights” flyers at a Greyhound station in Spokane, Washington, where border agents routinely perform onboard checks and where 37 passengers were taken into custody last year.

Because the Fifth Amendment grants passengers the right to remain silent, they are not legally obligated to answer officers’ questions—although refusing to do so has almost always led to arrest. The ACLU realizes that refusing to answer is a tough call for most people, but believes that if more passengers, particularly U.S. citizens, asserted their right to remain silent, it would be easier for the most vulnerable among them to do the same.

“We are asking that Greyhound require [border agents] to have a warrant to question passengers.”

“Greyhound is in the business of transporting its passengers safely from place to place,” the ACLU wrote in the letter to the company’s president and CEO, Dave Leach. “It should not be in the business of subjecting its passengers to intimidating interrogations, suspicionless searches, warrantless arrests, and the threat of deportation.”

For its part, Greyhound has said it is “required” to cooperate with agents, referring to statutory language stating that “within a reasonable distance from any external boundary of the United States,” CBP may, without a warrant, “board and search for aliens . . . any railway car, aircraft, conveyance, or vehicle.”

A CBP spokesman said Border Patrol is responsible for securing the borderbetween ports of entry. “For decades, the U.S. Border Patrol has been performing enforcement actions away from the immediate border in direct support of border enforcement efforts and as a means of preventing trafficking, smuggling, and other criminal organizations from exploiting our public and private transportation infrastructure to travel to the interior of the United States,” a spokesman said. “These operations serve as a vital component of the U.S. Border Patrol’s national security efforts.”

While the U.S. Supreme Court has consistently upheld the Border Patrol’s authority to stop and search people in the zone, it has placed some limits on their powers, requiring agents to have probable cause—a reasonable suspicion—to believe someone committed an immigration violation.

But the ACLU said agents don’t even claim to have probable cause and disputes that Greyhound is obligated to legitimize such raids by consenting to them. What’s more, the organization said these Greyhound trips have been entirely domestic, having nothing to do with border crossings.

“Greyhound has a choice,” said Enoka Herat, Police Practices and Immigrant Rights counsel for ACLU of Washington state. “Are they going to require CBP have a warrant in order to question passengers, or are they going to throw their passengers under the bus?”

The ACLU has documented stops in cities from New York to Arizona, Florida to Michigan. In January, agents arrested a father and son traveling on a Greyhound bus from Seattle to Montana, even though the son had valid Deferred Action for Childhood status and the father never gave the agents any information about his immigration status. They were asked: “Are you illegal?” and “Do you have your documents on you?”

While border patrol officials say they ask all passengers the same questions, including country of citizenship, the ACLU believes agents are engaged in racial profiling, based on its review of cases.

For example, CBP data obtained by ACLU in Michigan shows that 82 percent of foreign citizens stopped by agents in that state are Latino, and almost 1 in 3 of those processed are, in fact, U.S. citizens.

YES! Magazine is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 International License.

Lornet Turnbull is an editor for YES! Magazine and a Seattle-based freelance writer.