DOUGLAS, Ariz.—Public Works director Lynn Kartchner guides his city pickup truck down the overgrown, littered alleys of the Bay Acres mobile-home community in search of raw sewage.

Bay Acres’ small lots were carved from the desert 10 miles north of the Mexican border in the 1970s without any sewer connections, requiring each trailer to be connected to a septic tank and leach field. But septic systems built into clay-laden soils could only last so long. They were destined to fail.

While some homes are well kept, many bear the classic trappings of slums, including chained pit bulls guarding dilapidated singlewides and makeshift auto-repair businesses in back yards.

It doesn’t take Kartchner long to find his target.

Black sewage seeping from a failed septic system oozes into the alley, pooling in tire ruts. The black water indicates it has turned “septic,” meaning the water has become dangerously polluted.

“There’s overflows of effluent all over the place,” Kartchner says. “You’ve got dogs and kids out there playing in it.” The community, he says, has had outbreaks of cholera and hepatitis and there is worry that polio could appear.

A Cochise County Health Department official later downplays that assertion, saying no “clusters” or disease “outbreaks” related to sewage exposure in Bay Acres have been reported to the county.

“Is it a risk? Absolutely,” says Carl Hooper, a Cochise County environmental health specialist. “Is it a concern? Absolutely.” Otherwise, he says, he wouldn’t be going down there every month and depositing chlorine tablets to disinfect the contaminated water.

Despite more than $10 billion in environmental infrastructure investments along both sides of the border by the United States and Mexico since the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994, many communities ranging in size from Tijuana to Bay Acres lack safe wastewater-treatment systems, threatening the public health of millions of people on both sides of the border.

“It’s definitely a public-health risk,” says Kelly Reynolds, an associate professor of public health at the University of Arizona. “If you look, historically and currently, at any developing country that doesn’t have some dependable infrastructure for sewage containment and treatment, there’s always a higher level of morbidity and mortality” from waterborne infectious disease.

Failing or nonexistent wastewater treatment systems on either side of the U.S.-Mexico border can impact public health on the other side, particularly if groundwater is used for drinking water, as is common in border communities.

“The way water moves underground, the way sewage moves underground, there’s no differentiation between where the border is,” Reynolds says. “There is definitely the potential for cross-contamination on either side of the border.”

Most communities along both sides of the border lack the financial resources to build wastewater-treatment systems, which can cost tens of millions of dollars and more. Communities are forced to rely heavily on federal grants and loans.

The Trump administration and Congress are cutting back on key infrastructure funding programs and, in some cases, seeking to eliminate all spending. The North American Development Bank, which is jointly owned and operated by Mexico and the United States, is facing a sharp reduction in lending unless both nations increase their capital contributions. The Environmental Protection Agency’s primary grant fund for border infrastructure projects is nearly depleted, and the Trump administration and House Republicans are requesting no additional money.

Without continuous investment in upgrading, maintaining and expanding facilities, wastewater systems fail. Geography then takes over and untreated sewage flows downhill—usually from higher-elevation Mexican border towns into their sister communities in the United States. The impact is felt border-wide, from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico.

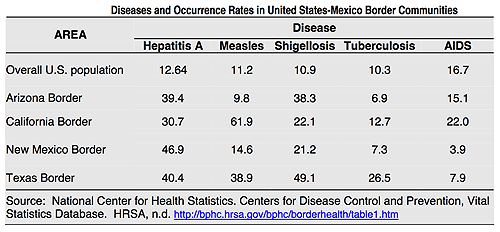

In Arizona border communities, waterborne diseases such as hepatitis A and shigellosis, occur at more than three times the rate in the rest of the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

Hepatitis A is a liver disease associated with unhealthy wastewater disposal and the use of inadequate or contaminated water. Shigellosis is a diarrheal disease often the result of poor sanitation, lack of water or wastewater facilities, or the use of contaminated water and food. It is common in poverty-stricken communities such as Bay Acres.

The tale of wastewater treatment, or the lack thereof, in two small Arizona border towns provides insight into the complex political, financial, regulatory and emotional factors that have allowed a festering public health menace to continue for decades.

A novel proposal by a third Arizona border town offers a possible solution, but it would require cooperation at the presidential levels of both countries, a prospect dimmed by President’s Trump harsh rhetoric toward Mexico and demands for a $25 billion border wall.

Mystery Sewage Flows

After decades of delays, the city of Douglas plans to install sewer lines in Bay Acres to eliminate the septic systems on 342 lots. But first it must expand its wastewater treatment plant, which operates near, and occasionally beyond, its 2 million gallon-per-day capacity.

The plant abuts the Mexican border immediately north of the much larger Agua Prieta, Sonora. The treatment plant is wedged between the border fence and hills of black waste rock called slag, generated decades ago when Douglas was the hub of a major copper-producing region in southern Arizona. At the time, a Phelps Dodge Corp. copper smelter was one of the largest single-source sulfur dioxide polluters in the United States. When it closed in 1987, the surrounding community went into economic decline. Now one of the area’s biggest employers is a state prison.

By the late 1990s, the city couldn’t afford to upgrade its 80-year-old wastewater collection system, water-delivery network or wastewater-treatment plant. Failing septic tanks were becoming a health hazard in places like Bay Acres.

The North American Development Bank helped arrange for more than $8 million in financing in the early 2000s, allowing the city to rebuild its water and sewer connection network and make improvements to the treatment plant. But there wasn’t enough money to hook Bay Acres up to the improved system.

The Bay Acres residents are finally about to see change. The development bank, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Arizona Water Infrastructure Financing Authority are helping the city finance a $16.3 million project to expand the treatment plant to 2.6 million gallons a day and connect Bay Acres.

Douglas City Manager Jim Russell says construction on the treatment plant is expected to begin later this spring. The improvements can’t come soon enough.

Kartchner, the Douglas public works director, told The Revelator on two separate occasions that untreated sewage is appearing in the Douglas wastewater discharge pipe immediately after it crosses under the border wall into Agua Prieta.

The United States and Mexico have a longstanding agreement that Agua Prieta would accept treated wastewater from Douglas and use it to irrigate farms. But releases of untreated raw sewage would violate the binational agreement.

Kartchner insists that the Douglas wastewater facility is not the source of the untreated sewage. Instead he blames Mexico.

“There is no untreated water that goes through there,” he says referring to the Douglas wastewater-outfall pipe. “There’s a few thousand (gallons) that come up from Mexico and join our line as it crosses the border, but that’s their raw sewage, not ours.”

Renata Manning, the North American Development Bank’s director of projects, says she was not aware of any raw sewage in the Douglas outfall pipe until told of Kartchner’s comments. She contradicted Kartchner’s explanation that it was coming from Mexico.

“The (Agua Prieta) sewage collection system does not intersect with the Douglas outfall pipeline,” she says, adding that Agua Prieta city officials also confirmed this on Mar. 1. Manning says the bank is “not aware of the source of the wastewater that may be appearing in the outfall box on the Mexican side.”

In late February The Revelator observed what appeared to be feces in a cement junction box where the Douglas outfall pipe enters Mexico just feet away from the border fence. Douglas’ 20-inch diameter outfall pipe connects with a 10-inch Mexican pipe that carries the Douglas effluent underneath a two-lane dirt road and into retention ponds about 40 yards south of the border fence.

The junction box is in disrepair and overflow wastewater was observed leaking from it and flowing into a ditch between the border wall and a nearby street.

A spokeswoman for the U.S. section of International Boundary and Water Commission, which is part of the State Department, stated on Tuesday that the agency sent engineers to inspect the outfall and “they did not find any sewer pipe connection to the outfall sewer line or structure, or any evidence of raw sewage in the discharge flow.” The commission provides binational solutions to issues that arise regarding boundary demarcation, national ownership of waters, sanitation, water quality, and flood control in the U.S.-Mexico border region.

Erin Jordan, an Arizona Department of Environmental Quality spokeswoman, says the Douglas wastewater treatment plant is in compliance with state regulations and “is not discharging raw sewage.” The state, however, does not have jurisdiction across the border to inspect the junction box, she says.

Margot Perez-Sullivan, an Environmental Protection Agency Region 9 spokeswoman, says it is possible that stagnant water from the wastewater holding ponds is backing up in the sewage junction box. “There is no raw sewage discharge from the U.S. nor is there any connection between the Agua Prieta sewer system and the junction box,” she says.

Douglas City Manager Russell stated in an email on Wednesday email that the city “is not discharging, in any way, any waste into” Agua Prieta. Russell states that the city believes any raw sewage showing up in the Douglas outfall is coming from Agua Prieta sewage pipes that drain into the wastewater holding ponds and untreated waste is backing up in the outfall.

It could not be independently confirmed Wednesday whether Agua Prieta has sewage pipes that dump into the wastewater reservoirs.

If raw sewage is being released from the United States into Mexico it would show how difficult it is for both nations to properly manage waste flows at the border. This would also signify the need for more cooperation at a time of high political tensions between the United States and Mexico and declining funds for improving environmental infrastructure along the border.

“The irony here is that it is usually the United States that finds itself at the receiving end of sewage flows that cross or join the boundary, as seen at Laredo, Texas, Nogales, Ariz., Calexico, Calif., and San Diego,” says Steve Mumme, a professor of political science at Colorado State University, where he specializes in comparative environmental politics and policy with an emphasis on Mexican government and U.S.-Mexican relations.

“If this is a chronic problem, Mexico is well within its rights to ask the U.S. to fix it,” he says.

While the reports of raw sewage in the Douglas outfall remains a mystery, residents in Bay Acres provided a mixed reaction to having the community finally hooked up to the sewer system.

Miguel Ochoa, who has lived Bay Acres for 10 years, says it is “very good” that the septic tanks will be removed because bad smells often occur at night and there are a lot of cockroaches in the neighborhood, which he blames on the open sewers. The new sewer system, he says, will encourage homeowners to upgrade their properties.

But other residents in the impoverished community were more worried about the additional cost of having to pay $40 a month for city sewage hookups rather than free disposal in septic systems—even if they are leaking raw sewage.

“After they do this we will start paying and I think that will be a heavy impact,” says Norma Loreto, who has lived in Bay Acres for more than 20 years, and shares a trailer with her son, daughter-in-law and grandson.

Raw Sewage Contaminates Twin Border Towns

Less than 30 miles west, in the twin border towns of Naco, Sonora, and Naco, Ariz., raw sewage has intermittently flowed from Mexico into the United States for decades. The untreated sewage spills over from sediment-filled treatment ponds on the east side of the Sonoran town and from sewer manholes on the west side of town.

The Naco, Sonora, wastewater and potable water-supply system was upgraded in the late 1990s with $200,000 in North American Development Bank funds and a $454,000 Environmental Protection Agency grant. The wastewater system, however, is once again failing from a lack of maintenance.

Since the Mexican town is at a higher elevation than its sister city, the sewage flows beneath the border fence and, depending on the flow rate, into Greenbush Draw, an ephemeral stream that runs within 600 feet of the primary drinking water wellfield for communities north of the border, including nearby Bisbee.

On the west side of the Sonoran town, workers have punched holes in the sides of manhole standpipes to prevent raw sewage from backing up inside homes, allowing it to discharge directly on the ground.

In late February raw sewage was observed pouring out of the side of a manhole pipe about 15 yards south of the border fence. A stream of sewage flowed down a dirt road in Naco, Sonora, before turning north beneath the border fence.

On the east side, sewage could be seen draining from the holding ponds and flowing beneath the border fence, where it collected in a low spot on a Border Patrol dirt road. During heavy flows the sewage crosses the road and drains into the desert toward Greenbush Draw, says Hooper, the Cochise County environmental health specialist.

During a late February inspection of the site by The Revelator, the overwhelming stench from the untreated sewage made it uncomfortable to be nearby for more than a few minutes before a headache set in.

Hooper routinely places disinfecting chlorine tablets in pools of sewage north of the border. Nevertheless, Hooper says increased levels of fecal coliform bacteria have been detected in Greenbush Draw. The local water utility is putting the maximum allowable amount of chlorine into drinking water drawn from nearby wells.

The raw sewage flows have recently been averaging about 60 gallons per minute, but Hooper says there have been surges where more than 6,000 gallons a minute of untreated sewage is released into the United States.

“Depending on the flow rate, it could go a couple of hundred yards or up to a mile and quarter,” Hooper says. During the heavy monsoon summer rains, the sewage can be swept about 20 miles down Greenbush Draw into the environmentally critical San Pedro River.

Last summer heavy rains unleashed a torrent of raw sewage from Mexico that flowed into Greenbush Draw and through a nearby cattle ranch. The incursion attracted widespread press coverage, and Arizona Sens. John McCain and Jeff Flake, along with Rep. Martha McSally, sent joint letters complaining about the situation to the EPA and the International Boundary and Water Commission.

“This flow of sewage poses a health, safety, and economic risk to Arizona’s vulnerable border towns” the joint letter stated, “and we are greatly concerned about the lack of response of the federal agencies tasked with the oversight of this issue.”

The International Boundary and Water Commission provided Naco, Sonora, with a pump to help reduce the amount of sewage in sedimentation ponds and the EPA provided $10,000 to help defray emergency repairs.

But the repairs have failed to stem the untreated sewage flows.

Hooper says one potential solution to the problem would be to connect the Naco, Sonora, wastewater system to the Naco, Ariz., system, which has capacity to handle the overflows. This could be done with only 300 feet of pipe at a relatively low cost, he says.

The Naco Sanitary District, which operates the Naco, Ariz., wastewater collection and treatment system, rejected the proposal last fall during a contentious meeting fraught with harsh overtones against allowing Mexican sewage into the treatment system.

Hooper says “they almost took my head off” when he suggested the proposal.

Naco Sanitary District general manager Rosa Ramirez says the board was “not necessarily opposed” to the idea but wanted more details on how Mexican sewage would impact their wastewater treatment system, particularly if toxic chemicals were present. “We were concerned not with just the sewage but what else was coming through,” she says.

Ramirez confirmed that political opposition to accepting sewage from Mexico was part of the reason the district did not agree to the proposal. She declined to elaborate and referred The Revelator to district board president Jim Dwyer, who in turn declined to comment.

Board member David Loyd said he another member of the five-person board wanted to take action to address the problem. “Speaking personally, the board was regressive,” Loyd says. “Considering the conditions, personally, I and one other member felt that we missed an opportunity to be progressive.”

Congressional finger-pointing and a lack of adequate funding to construct environmental infrastructure, along with a refusal by the Naco Sanitary District to treat sewage spills from its neighbor, means untreated wastewater will continue to flow from Naco, Sonora, into Arizona for years to come.

“We all know what needs to be done but folks who could potentially be part of the solution are often the same ones who say we don’t want (to process Mexican sewage) here,” says Hooper. “‘It’s going to ruin my property values.’ There’s a laundry list of excuses that are out there.”

Bisbee Proposes a Radical Idea

A common problem in Mexican border towns is the lack of qualified personnel and money to operate and maintain wastewater-treatment systems.

Municipal elections are held every three years, and a new mayor may appoint unqualified political supporters to jobs that require technical training. Many impoverished Mexicans, meanwhile, are reluctant or unable to pay their monthly water and sewer bills. Local politicians, in turn, may use promises of low utility rates to get elected.

This can result in situations where Mexican utilities lack the funding and expertise to manage wastewater systems—just like in Naco, Sonora.

“They don’t have the money or the expertise to man a modern plant and they don’t have the money and wherewithal to manage what they have,” says Andy Haratyk, Public Works operations manager for Bisbee.

Rather than browbeat Mexico and demand political, financial and technical reforms that could stop the sewage from flowing across the border but are unlikely to occur anytime soon, Haratyk is proposing a solution.

“We will take your water,” he says. “We will bring it to our plant and treat it and we get to keep the water to either sell or to sell discharge credits” for replenishing the ground water basin. “That will be how we recoup our costs.”

Bisbee’s plan would require the North American Development Bank and EPA to provide the city with approximately $20 million spread out over several years. This would allow the city to add additional capacity to treat about 500,000 gallons a day of wastewater from Naco.

Haratyk emphasizes that Bisbee’s proposal to treat Naco’s wastewater would be “at no cost to the city of Bisbee or the citizens of Bisbee. Not a penny.” The plan would also not require any payment from Naco residents or the Sonoran city, both of which are hard-pressed for money, he says.

The Bisbee expansion would cost about one-third of what it would take to construct a new wastewater plant in Naco, Sonora, which lacks the technical manpower to run a new plant and the financial strength to maintain it.

“What’s important to me is that we can’t allow this to continue to be happening for the health, safety and welfare of our citizens,” Haratyk says. “This is the least expensive way to protect the United States of America and the people I live with.”

One major challenge is that plan will require a treaty with Mexico, because wastewater that could theoretically be reused in Mexico would instead be transferred to the United States, he says.

Haratyk is hopeful that the EPA will fund a feasibility study to firm up the plant’s design and overall cost. If all the details can be hammered out, including a treaty with Mexico for the water, he says the project would take about a year to 18 months to complete.

The North American Development Bank is recommending that the EPA fund a $75,000 technical study on how to address the Naco, Sonora, wastewater needs. “As part of the analysis, we will include the Bisbee treatment option as an alternative,” Manning, the bank’s project manager, says.

Manning calls Bisbee’s proposals “an interesting long-term option,” but she adds that there are several major hurdles to overcome, including obtaining presidential approvals to transfer water from Mexico to the United States.

“The high implementation costs for that option, along with structuring an affordable agreement between the two utilities, may also be significant challenges,” she says.

The political, financial and cultural challenges facing small communities like Douglas and the twin Nacos are repeated in many border communities that lack the financial ability to construct wastewater-treatment systems without assistance from the two federal governments.

“We’re coming at it from a public-health perspective that this is an issue that doesn’t matter what side of the border you live on,” says Hooper, the Cochise County environmental health specialist. “We need to live in a healthy community and this is what it is going to take to get there.”

This is Part II of The Revelator’s “A Border Betrayed” investigation.

John Dougherty is the investigative journalist for The Revelator. An award-winning reporter with more than 35 years’ experience covering environmental, political and economic news, he has worked for weekly and daily newspapers including the Dayton Daily News, The Phoenix Gazette and Phoenix New Times. His freelance work has appeared in The New York Times, High Country News and The Washington Post. John has produced two documentary films, “Cyanide Beach” and “Flin Flon Flim Flam,” about the efforts of two Canadian companies to build the proposed Rosemont Copper Mine in southern Arizona. John loves the water and spends free time kayaking, swimming and traveling the backroads of the American West and Baja.