In mid-May, this year’s Pulitzer Prizes were announced, and as I scrolled down the list of recipients, I was surprised and delighted to see that the award for music had gone to Anthony Davis’ opera The Central Park Five, its libretto written by my longtime friend and colleague Richard Wesley. The piece tells the now well-known story of the five innocent young men falsely accused of rape and assault by police and much of the public, including Donald Trump.

Two weeks after the Pulitzer announcement, George Floyd lay dead in Minneapolis, a policeman’s knee to his throat. Within days, despite the COVID-19 pandemic, protests grew around the world as Black Lives Matter and many others rose up against police brutality and social and economic injustice.

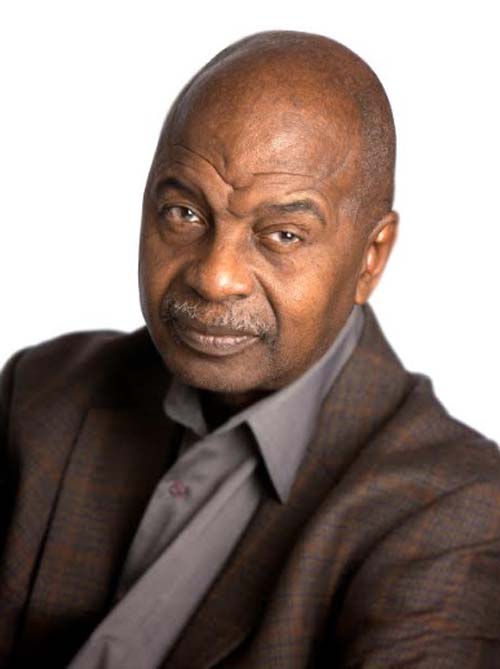

I thought once again of Richard Wesley and the parallels of his life, the arc of civil rights in America and the fight for equality. He grew up in Newark, NJ, and was present during the 1967 uprising there. He attended Howard University at a time of tremendous change and turmoil, the time of the March on Washington, the Birmingham church bombing, the rise of the Black Panther Party. His writing career took off in the sixties and seventies as Black Power, Black Theater and the Black Arts Movement were blossoming. He was an eyewitness to it all.

With his award-winning plays, including The Mighty Gents and The Talented Tenth; and such movie and television scripts as Uptown Saturday Night, an adaptation of Richard Wright’s Native Son and Mandela and de Klerk, Richard Wesley has devoted himself to telling stories about the Black experience. He continues to this day, scripting the aforementioned Central Park Five, teaching at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts and recently publishing a memoir, It’s Always Loud in the Balcony (Applause Books, 2019).

Given his experience and knowledge, I wanted to talk with him about his life and work and his reactions to what’s happening today in the United States—how similar it is to events of the past and how different. We first spoke just as the deaths of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin, and Daniel Prude in Rochester, NY, had occurred, and more nationwide demonstrations against police were underway.

“It brings back a flood of memories,” Wesley said of the protests. “Most of the people in my age group are so very proud of these young people marching. We wish that we could go out and just hug each and every one of them and give them nothing but every ounce of support that we have. They’re us 50 years ago. They’re doing precisely what we did.

“For me personally, the fact that they are doing precisely what we did makes me want to go to them and say, “Look, don’t do precisely what we did, instead build on what we did and learn from what we did. Don’t repeat history, make history. Build on history…

“It’s a question now of these kids taking what we did from the ’60s and expanding on it and making something even better and stronger. And I have no doubt that they will.”

He sees a real impact, a shift in American opinion, and even an effect on greater Black involvement in movies, theater and TV, a new generation of storytellers. As for the November 3 election, “I think a lot of people are going to come out of their houses, they’re going to risk their health, and they are going to stand in line at those one, two or three voting places that are available to them, and they’re going to stand in line and vote. And they’re going to vote by the hundreds and hundreds of thousands…

“How many thousands died, how many millions became infected, because of what [Trump] did, and because of the corrective measures he failed to follow? So yeah, people are going to be giving a lot of side-eye to this President and the politicians who support him. And if that happens, then Donald Trump will be a lame duck president after November 3rd. And no matter what he tries to do on January 20, 2021, Joseph Biden will be president of this country. And then it’s going to take years to fix up the mess that has been made to redress all of the things that have gone wrong.”

Our Zoom conversation covers the contemporary crisis seen through the career and life of a Black writer who has lived through decades of racial struggle, who has been in the presence of some of the great pioneering creative and activist voices of his community—including his own—and who has reflected and utilized much of what he has experienced in the body of his work. You can read the entire interview below. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Richard, how are you, and how has this pandemic affected your own life and work?

Physically I’m doing fine. I think psychologically, I’m up and down. Sometimes I find myself a little morose, uncertain about how things are proceeding… My daily routines, all of them have been completely destroyed, totally thrown off. And I’m having to learn new habits and new ways of keeping myself active physically.

Creatively, I’ve been doing a lot of writing since the start of the pandemic. I’ve written a couple short pieces for presentation via Zoom. And that’s been exciting. It’s given me some ideas about how one writes scripts for this particular technology. It’s so different from television, it’s different from film, yet it also seems to rely, I think, on some of the same creative processes that might’ve gone into serious writing for network radio 70 and 80 years ago.

You have to depend on the audience’s willingness to suspend reality on the one hand and use their imagination on the other. At the same time, you still have access to contemporary technologies in terms of developing artificial backgrounds, where you place the actors, etc. But you’re also fundamentally using a head and shoulder shot, just like the two of us now in the frame, and you’re writing in a way in which the actors are not necessarily interacting directly with each other but with the audience. It’s a kind of hybrid screenwriting. And I’m very excited about what I’ve been able to accomplish so far, what I’ve learned from it, so I’m just going to keep moving in that direction.

I want to talk to you first really about your involvement with this Anthony Davis opera, The Central Park Five, which just received the Pulitzer Prize for music. You wrote the libretto. How did you come to be involved with this project? What was it like striking out into what I think is new territory for you?

It was completely new territory for me. My involvement with it was through the Trilogy opera company, a small company headed by the singer Kevin Maynor over here in Newark, New Jersey. And in its original incarnation, the project was called Five. The libretto that I wrote at that time was developed entirely from material in the public domain. There were time constraints because of the grant that Kevin had received. We had a very short time in terms of my being able to write the script, then the libretto being sent off to [the composer] Anthony Davis, him being able to musicalize and then us getting into rehearsal and getting it up on its feet.

There was no opportunity to interview any of the five young men, no opportunity to get into the kind of in-depth research that I might like to have had the opportunity to do. I just used what I had in front of me and created a libretto from that. Rather than trying to recreate reality, I decide to write the script in an impressionistic format, and that allowed me a lot of leeway in terms of going in and out of reality, in and out of people’s consciousness, getting into the inner lives a little more deeply.

I thought more of writing the script as a kind of performance piece and a little bit of Brecht’s epic theater concepts from nearly a hundred years ago came in handy. It was kind of a pastiche of all of that. And certainly Melvin Van Peebles’ ideas for Ain’t Supposed to Die a Natural Death, his Broadway show from 1970. Those were all the influences that went into the writing of the libretto itself.

Were you able to make use of your own memories of the incident in 1989?

Yes. I think when it actually happened, I was in Los Angeles working on some projects there, but then when I came home to New Jersey, the reverberations of that being only 12 miles from the incident itself, and at the same time the feelings that emanated from all of that, all went into the writing of the script. I had to take myself back to that time. And then I became the victim, Tricia Meili, the woman who was attacked; I became the five men, Kevin Richardson, Antron McCray, Raymond Santana, Korey Wise and Yusef Salaam, and when that happened, I had to think about how I felt as a black male, what I remembered viscerally from hearing and reading about Emmett Till, when I was ten years old, hearing and reading about the Scottsboro Boys, which happened even before I was born.

All of these different feelings came into the writing of the script and then putting myself in the shoes of various imaginary white people who were reading about this in the newspapers, experiencing it as a news broadcast via television. What must’ve been going through the minds of a white person who lived on East 90th Street near the entrance to the park, knowing the area where the woman was attacked, hearing, maybe even having been out that night when there were all those teenagers in the streets going in and out of the park.

And so I used all those feelings and all those assumptions to write lines that made up the opening of the libretto itself.

Do you have memories of the ad that Donald Trump took out calling for the death penalty?

I didn’t know about Donald Trump’s ad until years later, and I happened to see a reproduction of it. And it was shocking. And then even years after that, to know that even when he knew that they were innocent, he never apologized, he never retracted his statement. All of that, it’s not something that’s easily forgotten.

Let’s talk about your book. You’ve had such a distinguished career in theater and films. What led you to write this memoir, It’s Always Loud in The Balcony, and why that title?

It didn’t start as a memoir. It was supposed to be a very academic and scholarly nonfiction book on the history of the Black Arts Movement, Black Power…

I was wondering about that.

… From the mid ’60s forward. But my editors and the publisher, they all felt the book is really dry and kind of uninteresting, and you were there, why don’t you put more of yourself into it? Well, I saw what they probably meant, I went back and did a rewrite and made the language a little more accessible and the note I got back was, “No, we mean, we want you to literally put yourself into it.”

Once I did that, then it became a personal history and I kept saying, “I’m not going to write a memoir, I’m not going to write a memoir.” And well, yeah, it turned into one.

And why this title?

It’s Always Loud in the Balcony—when you go to a lot of shows, especially when you’re going to the Apollo Theater to see a show, the people up in the balcony were usually the ones who were most likely to heckle the emcees, who, when they see an act that they don’t particularly like, they’re always the ones quickest to express their dissatisfaction.

They’re people who work very hard, they spend hard-earned money to come and see a show, they’re stuck way up in the balcony, they can barely see anything and then the show turns out not to be good at all. And so, yeah, they’re going to speak up. They’re the dissatisfied ones. Social movements are sparked by the dissatisfied ones, And the black theater movement itself started among the people who were dissatisfied.

Contemporary black theater in some ways owes its spark, not simply to Amiri Baraka’s play, Dutchman, from 1964, but from a 1966 essay about how it may be time for a Negro theater. It was written in The New York Times by playwright Douglas Turner Ward [“American Theater: For Whites Only?” September 25, 1966]. It was in its own way a manifesto, and an outgrowth of that was an interest in finding or developing these heretofore unheard voices. That’s how Doug [Turner Ward] got a grant from the Ford Foundation to start the Negro Ensemble Company.

Ford was also involved in grant money that went to Robert Macbeth further uptown in Harlem to found the New Lafayette Theater. And there were a number of other theater companies that grew out of the efforts by the Ford Foundation to plant these seeds of artistic development. The dissatisfied ones in the balcony, the Douglas Turner Wards, the Amiri Barakas, the Ed Bullins, the Sonia Sanchezes, they’re the ones who were loud in America’s theatrical balconies.

The New Lafayette is where you worked, right?

Yes, I was at the New Lafayette. The theater was founded in 1966, 1967. I joined the Black Theater Workshop, which was a division of the theater, I think in the fall of 1967, and then became a member of the theater itself in 1970.

But you started out wanting to be a television writer.

Well, I’m a baby boomer, so we’re the generation that pretty much made sure that television was going to be a thing. Every household had to have one because of us kids, and I grew up on TV. Certainly the anthology series of the ’50s, Dick Powell’s Four-Star Theater anthology series, the live theater presentations, which particularly had a very strong effect on me even at the age of 10 and 11 years old. Armstrong Circle Theater, Kraft Playhouse, US Steel Hour—these were the shows I watched all the time. And writers like Abby Mann and Rod Serling and Paddy Chayefsky became names that were very, very familiar to me. I knew if I saw their names in the credits I was going to see something interesting.

And that also is an indication of just how much of a writer I was and didn’t realize at the time. I was looking to find out who wrote the script. To this day, I cannot tell you the name of most of the directors of those shows. And that was an era when people like Sidney Lumet and John Frankenheimer were establishing their careers. And I was looking right past all of that straight to the names of the writers. So whenever I saw a name like Abby Mann and certainly Paddy Chayefsky I was paying attention.

And I was dead into The Twilight Zone because I recognized Serling’s name immediately. And Twilight Zone ultimately became my favorite television show. And that was the show I studied most closely in terms of how to write really interesting stories.

One of your professors said, “If I can teach you to write for the stage, you’ll be able to write anything.”

Owen Dodson, the chair of the department, he was a fairly well-known poet and a writer at the time. And yes, that’s exactly what he said: “Child, if I can teach you to write for the stage, you’ll be able to write anything.” He said it dramatically, fixed me with a stare and peered over the top of his glasses. And I said, “Well, okay.” And I stayed.

My mother had a sister and two brothers who lived in Washington at the time. And so I knew if I went to Howard, I’d always have family that I could run to if things got difficult. That was a big reason. And also at the time Howard in the brochure had indicated that they had courses in writing for television and film. It was supposed to be taught in the drama department. So that was another reason why I applied. Not the least of which also was because Howard was the only college that I was applying to at the time that didn’t require a cash deposit when you returned the application.

I’m fascinated by the fact that you entered Howard in the fall of ‘63. So it was just after the March on Washington, but just before the assassination of Jack Kennedy. How did those events impact you and shape your thinking?

I think, as I write in the book, there was still a buzz in Washington. Our orientation as freshmen began just weeks after the March itself. You could still see posters up on some of the walls and telephone poles announcing the March. There were people there talking about the march route. In the aftermath of the March there were signs all over DC at the time. And my newfound friend John Richards, one of my freshmen classmates, and I, when we walked from the campus down 7th Street into downtown Washington, it was everywhere.

It was very exciting. There was a real sense in the air of new possibilities and a real change. Everything about the Kennedy administration, it carried its own electricity for young people at that time. Because we had a president who didn’t look so much like a dad the way Eisenhower did. He looked more like the cool big brother who really made it.

In terms of civil rights, he was there, in terms of the New Frontier, the space program, with the Peace Corps. These were things coming out of the conformist ’50s that just promised whole new vistas and whole new possibilities. Everything seemed possible that particular late summer or early fall. And even though [there was] the bombing of the church in Birmingham, when the four little girls were killed, as horrific as that was and in spite of the assassination of Medgar Evers, just before I graduated from high school that previous spring, there was still this sense that there were other brighter, heftier promises going forward.

There were things that were going to be overcome, and there was just going to be a different America out there. And here I was, 18 years old, and I was going to be right at the beginning of it. And then the president was assassinated.

You were born and raised in Newark, New Jersey and you still live in New Jersey. You were present for the uprising in Newark in 1967. What are your memories of that?

That was right after my graduation from college, and I was home. In fact, I told my parents when I came home from Howard that you all don’t understand. Places like Newark are like a powder keg, it’s about to blow. I don’t think I fully realized that less than 10 days after I made that statement to them, Newark in fact really would.

It was deeply personal to me. My brother was managing a supermarket right at the epicenter of the rebellion itself. I remember being very worried about him because it was clear that there was shooting, there were crowds of people in the streets. There were already victims of gunshot wounds. We didn’t hear from my brother until well into the night, and then we found out that he was basically hiding at a friend’s apartment. They were all on the floor.

I remember the angst that my parents felt. I remember a certain grimness that I experienced. I was certainly aware of the possibility that something like that could happen

As I write in the book, three people that I knew growing up were killed during that time. My two younger cousins and my aunt and uncle lived in the Hayes Homes, which was a collection of apartment towers that was right across the street from the police precinct where all this gunfire, where the uprising itself started. And in those old newsreels that you see of the rebellion itself, occasionally you might see some film of some National Guardsmen crouched behind cars firing at tall buildings in the background. And then there’s images of bullets ricocheting off the facade of large stone buildings—those are the Hayes Homes. Those were the buildings that my aunt and uncle and cousins were living in at the time, and they were forced to stay on the floor.

I know that it had a terrible effect on my aunt because it wasn’t too long after that she had a nervous breakdown. And she had other emotional problems, because some of those gunshots were aimed at the building that she was living in. And Mrs. Eloise Spellman, the woman who was killed while she was cooking dinner for her children, she was killed by a stray bullet from a National Guardsman’s rifle because he thought she was a sniper. And that was the tower that was diagonally across from the one that my aunt and uncle were living in at the time.

How did seeing all this and hearing about it impact your work later on?

I’ve never really directly written about my experiences or memories of the uprising itself. But I think there have been residual effects. It’s had to have turned up somewhere in my plays and things. Particularly a play like The Mighty Gents or The Sirens, because both those plays definitely take place in Newark. And they take place right around the time of the rebellion itself, even though they don’t talk directly about it. But they talk about people who would have been in the middle of it had they actually been real characters. Another play, The Talented Tenth, about a black professional and former political activist in his youth who is now entering his 40s during the 1990s and experiencing a mid-life crisis, features another character, a young woman in her 20s, who was a child caught in the middle of the Newark Rebellion and has a completely different memory of those days, one that is neither rosy nor heroic.

You were very much immersed in the explosion of black theater in the ’60s and ’70s. What was the impetus for that? Why did so many theater companies emerge across the country at that time? And why were they so important to the black experience at the time?

Well, the area of black theater that I came from, we were the cultural arm of the Black Power Movement. We were the offshoot of the civil rights movement itself. After the Voting Rights Bill was passed in 1965, that was pretty much the culmination of the primary struggles of the civil rights movement; the next level after that had to do with, how do you use these newly acquired rights as far as voting is concerned?

How do you turn the right to vote in the South into a way to address the inequities there? And how do you turn this energy, this right to vote, into a real political power in the North? Newark was predominantly black going all the way back practically to the early to mid ’60s. The same was true of Washington, D.C., Philadelphia and Detroit—and certainly becoming true of New York City. Each ethnic group as it reached a certain critical mass has exercised that mass through the vote as a way of gaining some traction in the overall society. Every group has done it: Italian Americans, Irish Americans, Polish Americans, going back to the founding of the country.

Now, here was a time for black people to start doing some of the same things. And so what do we want to do with this vote and how are we going to use this vote to exercise our freedoms as citizens? That’s what Black Power was all about. But Black Power was not necessarily a movement that was the brainchild of Dr. King. We felt we owed our legacy more to Malcolm X, who was much more assertive and took a stronger stance, and I think it was more reflective of his urban setting. Dr. King was in the South, in the Jim Crow South, a very violent area of the country at that time for black people. And nonviolence as a way of political expression made a lot of sense there, but in the North, it was different.

There were not the same kind of Jim Crow constraints, certainly not overtly in the North, so the ability to speak our minds and the ability to have an eyeball-to-eyeball conversation with the white power structure came out of a different kind of psychological or emotional stance. Malcolm represented that stance far more than Dr. King did. So we started looking more toward Malcolm. Once we started looking in Malcolm’s direction, we started looking at other political influences, the liberation movements overseas. What were Chief Luthuli and Nelson Mandela and the African National Congress doing in South Africa? What was FRELIMO doing in Mozambique? What was going on with the political action movements and liberation movements in Angola? Their political philosophies were far more leftist.

So there was Marxist–Leninist thought, there was Chairman Mao and The Little Red Book. I think at least 40% of baby boomers in America, no matter what their race was, we could all cite the Little Red Book. That’s where all of that came from. It was all of that, and I guess, when Amiri [Baraka] and Larry Neal codified the Black Arts Movement in a publication, an anthology called Black Fire—Larry Neal has an essay that talks about Black Arts in there. And then later on in a special edition of the Drama Review where Neal expanded that essay and literally laid out a manifesto that structured an ideological platform for the Black Arts Movement.

We moved in that direction. Black Theater grew out of that. One arm of it, the political and culturally oriented black theater that was deep inside our African American communities. The Negro Ensemble Company, they moved in another direction that was very strongly based in art but was not quite as militant or ideological as what we were doing uptown at the New Lafayette.

You had these two opposing lines of thought, but everybody was moving in the same direction, which was this greater expansion of expression. We had a lot to say. We had a lot that we wanted to do. We had writers, we had tons of things that they wanted to write about. And there seemed to be no real room in mainstream theater for us at all. Whether it was Broadway, off Broadway or even the regionals.

And since they didn’t seem to have room for us, we had to create room for ourselves. And that’s also where theater came along. And then when you had the National Endowment for the Arts, particularly the expansion arts division of the National Endowment, and Rockefeller grants and the Ford Foundation grants, everybody was trying to make a contribution. Everyone was trying to get involved. The same way everyone wants to get involved to support Black Lives Matter today. Suddenly, we had the financial means and we had these spaces, storefronts and old converted movie houses and flatbed trucks that can move through the communities, and everything like that and the funding to support these spaces, so we went out and we made art.

There was conflict at the time between those who thought black theater should be exclusively for blacks and those who did not.

Yes, there was. There was a great deal of conflict. There were conflicts between the artists. Like I said, New Lafayette represented one train of thought, Ed Bullins and Bob Macbeth on this side, Robert Hooks and Douglas Turner Ward on that side. Each had a position about the direction the art should take, and each side was equally adept in advocating for their points of view.

At the same time we were all engaged in difficulties with those who were strictly politics. The ideologues, the brothers with the guns, that’s how I describe them in the book. And it wasn’t just the Black Panther Party, I know that’s the first thing that everyone runs to when you say brothers with the guns. But it wasn’t just the Black Panthers, there were others. There were black nationalist groups who were also armed. And they were committed to the idea of armed struggle. And we, the cultural nationalists, if you will, were not.

We felt that with the art that we were engaged in, we were busy trying to reconstruct the psychological lives of the black community. We were trying to get it to look inward, see themselves, rebuild themselves. And then we could start making decisions about the world outside, the world beyond us. The political brothers, the ones with the guns, they wanted direct confrontation: “We want to be at the table, if we can’t get a seat at the table, then we are going to turn the whole table over. And if you guys are not with us, then you’re against us and if you’re against us, you will be dealt with.” That was going on then, too.

So, as I said, there were those who felt too that emerging black theater should be exclusively for black audiences and others who felt, as I assume you did, that there should be a more diverse appeal.

Yes. That’s an argument and a debate that is still ongoing. It’s never been resolved. And I just think that it’s two contending thoughts that are going to have to exist side by side. And I think the times are going to dictate how that argument is going to be resolved going forward. American society as a whole is going to determine the end of that argument. Inside the community, it’s never going to be settled. Each side thinks they are absolutely right.

There’s one side that believes we have to do art for the people, for black people, black art for black people. We have to be able to speak directly to them. We can’t temper what we want to say. We can’t be worried about other people’s feelings. We can’t be worried about, is this going to offend one segment of the audience if we say that? We want to be able to express ourselves 100%.

Then you have the other side. You’re talking about ideological purity and we’re talking about trying to develop an audience and we’re trying to have everybody in on the conversation because we’re in this space with everybody else. Everyone should be able to experience our art. Our art is human, it is as expressive of the human condition as anyone else’s art, so why keep it confined? That debate is just going to go back and forth I think for the foreseeable future.

You just mentioned the times that we’re in now. And given that you were present for so much of the Black Power, Black Consciousness and Black Arts movements in the ’60s and ’70s, what do you think about what’s happened over the last few months since the death of George Floyd? How does it compare?

It brings back a flood of memories. Most of the people in my age group are so very proud of these young people marching. We wish that we could go out and just hug each and every one of them and give them nothing but every ounce of support that we have. They’re us 50 years ago. They’re doing precisely what we did. For me personally, the fact that they are doing precisely what we did makes me want to go to them and say, “Look, don’t do precisely what we did, instead build on what we did and learn from what we did. Don’t repeat history, make history. Build on history.”

And I think even to some degree, I heard last week Jim Clyburn, the House majority whip who also is a veteran of the civil rights movement from the ’60s, he said precisely the same thing. It’s a question now of these kids taking what we did from the ’60s and expanding on it and making something even better and stronger. And I have no doubt that they will.

I want to read to you part of this column that Charles Blow at The New York Times wrote back in early August. He was talking mostly about the involvement of whites and others along with black people in these demonstrations and other actions post the death of George Floyd. And he said, that his concern was that, “Much of what we saw in response to the protest amounted to performative gestures, symbolism that costs nothing and shifted no power. Some of what we saw was people cos playing consciousness, immersing themselves in the issue of the moment.” And then he said, “America has a sterling track record of dashing black people’s hopes.”

Yes. He stated it differently, but there are a lot of us who had very similar feelings in the late ’60s and early ’70s. The artists who, for instance, who were interested in black theater for black people, would have said something very similar to what Charles Blow was saying there. Because back then, one of the things that used to drive us crazy, and was a big reason why we never really got very close to the Weather Underground or the Yippies, or some of the other groups, the white groups at that time, was this nagging sense that the same kids who were frolicking in the ponds, in the rain at Woodstock, would eventually cut their hair, shave their beards, hang up the tie dye dresses and blouses, wash their faces, and the next thing you know they’re going to be in the banks rejecting our applications for home loans.

They’ll be the ones who suddenly will turn into the Tucker Carlsons of the world: “It was all just a moment in our lives, we’re grown up now and we’re going to move on.” And for us, that vision, certainly for those of us in Harlem at the time, that vision came true at the most interesting time around 1972, early 1973, when Richard Nixon ended the draft and suddenly all of the demonstrations in the streets, all of the strong push toward progressive politics seemed to literally quiet down.

All the young men who had drifted north of the border into Canada came sheepishly back into the United States, but there was still no strong drive coming up from the streets. All those kids who were out there, they suddenly turned into middle class America. And within 10, 15 years they had quieted down and were replaced by Dan and Marilyn Quayle.

Do you remember the speech that Marilyn Quayle gave at the onset of the 1992 political campaign? She basically denied the entirety of the anti-war movement, talked about how the anti-war movement was represented by only a small portion of the baby boom generation. The majority of that generation were the ones who were working two jobs, were the ones who had their noses buried in the books on college campuses to put their careers together so they’d be able to start an all-American life.

They were, she said, the ones who were part of the silent majority… But I remember hearing that speech and thinking back to our mistrust of those political alliances with the Weather Underground back in the ’60s.

They’re just what we always thought. There they are. Because 15 years ago, Marilyn Quayle had her hair halfway down her back. She was wearing sandals, then she was out in the streets and everything else with everybody else. Now, she’s a Republican wife and her husband is the vice president of the United States. And she’s somebody else entirely, and all that stuff is forgotten. And she’s pointing fingers.

I was involved in the anti-Vietnam movement and that was certainly our experience, too, with a lot of people. A friend of mine used to call it the Frisbee revolution because, he said, once the demonstrations were over and the hard work of organizing and lobbying against the war, when that came around, there were a lot of absentees.

I remember a contemporary of mine, Ben Caldwell, wrote a play about it. It was a short piece where you have all these true believers and you’re out front and you’re leading the revolution, and the police roll up the big gigantic cannons and you are ready to run headlong into the cannon fire. Because even if I fall, I know that people will continue on. We will turn those cannons around. And the police commander yells, “Fire.” And the cannon goes off with a loud boom. But when the smoke clears, it’s all dollar bills floating down to the ground. And as the revolutionary leaders are running forward, the masses behind them are stooped over on the ground scooping up as many of those dollar bills as they can.

So is that also your worry now?

I think it’s always a possibility. As excited as I am and happy for them moving forward, it’s always a possibility. But they’re the ones who are going to have to watch out for it. All of us older guys, the only thing we can do is advise them. What we can do is point to our own experiences, but I think this is something they’re going to have to go through. Also as I mentioned in the book, it’s a characteristic of America itself. It’s the way the system is constructed.

You have the billy clubs and the tear gas and the militarization of the police and the police violence and all of that in terms of putting down demonstrations, but the way in which America really handles its threats always involves money and who gets access to it. And our movements always get bribed out of existence… I think about how the Black Panthers became props for television commercials; Right On, R-I-G-H-T, within two years became W-R-I-T-E On, and it was being used to sell Paper Mate pens.

Everyone wanted to wear a black Morena leather jacket at one point. The minute that Johnny Carson or Dick Cavett, once they had Kathleen Cleaver or Huey Newton on as a late-night guest, the revolution had turned into something else. It’s not the same as Mao going all the way across to Yan’an province in exile and waiting for his chance to lead the Red Army back eastward to take Beijing. It’s not Fidel Castro hiding out to the point of starvation in the mountains in central Cuba before he manages to turn things around and seize power, drive Batista into the sea.

That’s just not how things are going to work in the United States. And no one has really figured out how to have a violent political revolution in America. At least not yet. You don’t know what’s going to come in the next four or five years. But that was something that I remember seeing and feeling very strongly in the ’60s and ’70s—the way in which revolution in this country became just another aspect of celebrity in America.

And of course my childhood hero, Paddy Chayefsky, he wrote about it and previewed it to some degree in the film Network.

I know it’s a little bit difficult because of the pandemic and so forth, but have you seen an impact of Black Lives Matter on the stage and in TV and movies? Is it impacting the entertainment industry?

In terms of some of the changes that I’ve seen, I’m really excited about the work of this young writer, Misha Green, with her show Lovecraft Country… There are elements that turned up in some of the writing in the Perry Mason series that HBO recently had. Lena Waithe with what she’s trying to do with The Chi over on Showtime.

And also with the elevation of more young executives of color and women executives inside the industry itself… These are new possibilities, and I think some it is an outgrowth of Black Lives Matter, which itself [has had a resurgence after] the horrific deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and so much else, right on up [to Jacob Blake,] the young man shot down at close range in Wisconsin. And now we have more police violence revealed to have taken place in Rochester. Black police chiefs in Rochester and Seattle have resigned in the wake of the revelations of suspected misconduct in their police forces, and their inability to address and/or change things in the departments under their command. And still the marches continue.

All of these things are having an effect on our country. And I see parallels with the ’60s, but at the same time I’m also aware that this is a new century. And the young people who are coming up, I know that they’re different because I teach them over at NYU in dramatic writing. Those kids, they have a different way of looking at the world, and the world itself has had such an impact on them.

They’re in the process of trying to figure out how to write a new set of rules that make the space that they have to live in livable. I’m interested to see what that’s going to be. I’ve been teaching for 25 years at New York University. And some of the students that I was teaching early on are now moving into positions of influence and they’ve really settled into their careers.

And I’m interested in seeing what that means in terms of how things are shifting and changing. And I think I can already see it. Not only them, but other people in their age cohort. Ava DuVernay is in their age cohort. Ryan Coogler is in their age cohort. The older ones that I taught from way, way back; Dee Rees was in the film department upstairs from me, and she’s making her presence felt.

I think the jury is still out. We still have yet to see all that’s changing… The freshmen I taught last year were infants when 9/11 happened. They’ve grown up with America at war every year of their lives right up to this very day. No other generation in this country has ever experienced anything like that. And it’s somewhere in the back of your consciousness. They’ve already lived through two economic upheavals, I mean, complete upheavals in their lives. And at the same time, they’re the first generation that spent eight years of their lives with an African American as president.

So Kamala Harris is not necessarily a surprise. Kamala Harris is something more of an expectation. And because of that, there are certain things that they’re going to expect of her that are going to be impacted by the other expectations they have about what all of this America is supposed to mean. They’re the ones who are going to inherit and have to figure out how to navigate this post-pandemic America that’s coming.

None of us can know until after the election exactly what that’s going to look like. These kids are the ones who are going to be the most affected by it because they’re going to live throughout most of the rest of the century. I even tell them in class—I know it goes in one ear and out of the other – they’re saying, ”What the hell is he talking about? That’s years from now, and I’m only 20! ” But with the modern advances in medicine and everything like that, a child born in 2001 has every expectation of living right through ‘til the end of the century, of living 100 years.

The same way that a person living to the age of 80 today is sort of like, well, that’s kind of normal. Toward the end of this century, living to be a hundred will be kind of normal. So that means, wow, in 2030, they’re going to be adults taking over the reins of control in this society. And then from 2030, all the way down to 2070, they’re going to be the voting bloc that determines the leadership, determines the legislative directions of the country, and determines, since I teach mostly screenwriters and playwrights, they’re the ones who are going to be controlling the images that come on out through whatever the medium is – holograms!

I think they won’t be doing TV anymore at all. Three dimensional images projected in some kind of special entertainment room in everyone’s house or apartment for all I know. And what are those going to be? All of it is going to come out of the tumult, I think, of the times that we’re living right now.

What are your feelings about the election at this point? You recently wrote that Republicans are not silent in the face of Trump’s outrages because they’re afraid, they’re silent because he’s giving them everything they’ve been clamoring for, for decades.

I think it’s true. And in fact, I’m convinced of it because last night on MSNBC in an interview, Scott Walker, the former conservative governor of Wisconsin pretty much said that. He said, “We love Trump because he’s given us everything we want.” And he cited the Supreme Court, he cited the corporate tax breaks, he cited Trump making a deal in Afghanistan to end the war there, he cited the appointments to the appellate courts, he cited the evisceration of the Voting Rights Act and voter suppression around the country. Although he used softer language, that was pretty much what he was extolling the virtues of.

That’s the battle we have to face. Yes, there are a lot of people who will profess to be upset with Trump, but at the same time they’re secretly very happy at what he has delivered. But for those of us who had a completely different vision of America and what its promises represent, their vision is a nightmare. There are more of us than there are of them and the question is, will we motivate ourselves in the face of all of this opposition to get out there and vote?

There are days when I am incredibly optimistic about that. I think a lot of people are really angry about what happened with the post office most recently, and with the president’s pretty much tacit admission that he was manipulating the postal service to thwart mail-in balloting. And I think a lot of people are going to come out of their houses, they’re going to risk their health, and they are going to stand in line at those one, two or three voting places that are available to them, and they’re going to stand in line and vote. And they’re going to vote by the hundreds and hundreds of thousands.

And now we have Bob Woodward’s book, with direct quotes from Donald Trump on tape, admitting that he knows and agrees that the coronavirus is airborne, saying this at precisely the time he was publicly decrying the virus as a “hoax,” at the same time he was contradicting and undermining the top scientists in this country, men and women whose job it was to provide us with the facts and information necessary to fight the contagion. And this guy was deliberately pushing policies that kept our country wide open and vulnerable at exactly the time we should have been shut down. How many thousands died, how many millions became infected, because of what he did, and because of the corrective measures he failed to follow? So yeah, people are going to be giving a lot of side-eye to this President and the politicians who support him.

And if that happens, then Donald Trump will be a lame duck president after November 3rd. And no matter what he tries to do on January 20, 2021, Joseph Biden will be president of this country. And then it’s going to take years to fix up the mess that has been made to redress all of the things that have gone wrong.

One of the things that I remember from the Reagan years, when Reagan became president, that comment that he made about government is the problem. That was, of course, an outgrowth of all of these efforts by Republicans and conservatives going all the way back to Robert Taft during the Truman administration to make people uncomfortable and distrust expansive government, to undermine the effects of Roosevelt’s vast expansion of the federal government, with Social Security and the FDIC and all the other great things that he did during the New Deal. [This was their way] of getting rid of the New Deal.

And so conservatives in this country have always gone after the government, beating down the government, putting it down—“You can’t trust the government…Government overreach, state’s rights, the government can’t be trusted, the government is inefficient. Market forces should determine the future of the country and the government should stay out of it.” And now we’ve got a president who has succeeded. He has undermined almost every branch of the federal government that we have taken for granted. And he’s made the government appear to be weak and unworkable.

He’s gone in, he’s eviscerated OSHA. He’s done a number on the EPA. Right now today, because of what he did with this plasma that he wants everyone to get involved with, he’s overridden the FDA and the CDC. Now we don’t know what’s approved and what is not. We don’t know who to believe. And when in our lifetimes, because we’re boomers, we’ve grown up with the FDA and the CDC and all of that. When have we ever not trusted the word of the FDA and the CDC? And now, we don’t know who to believe.

Listen, this has been so terrific. I could keep going on and on—we haven’t even had a chance to talk about your movie work and some of the other things… I’m hopeful that first, people will buy It’s Always Loud in the Balcony.

Well, please do.

And I’m also hopeful that, as you indicated, you might be writing a second book which would cover a lot of these other things. I should say that It’s Always Loud in the Balcony talks a lot about your work with Sidney Poitier and other film and theater projects. And I’m hopeful that the second book will deal with some of your later plays and some of the other films.

Well, yeah. When I first started the book, I had not expected to write much about my film work at all. But the powers that be in the publishing house said, “How can you write a book about the Black Arts Movement and not talk about black film and your involvement in it, Richard?” “I am, I am,” and so I started to get into it in this book, but then I was also running up against a publishing deadline and so that’s one of the reasons why it ends where it does… And I hope that I do have the opportunity to expand much further and talk about the times that I spent in Hollywood. And I look forward to that.

Thank you again.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 License.

Michael Winship is the Schumann Senior Writing Fellow for Common Dreams. Previously, he was the Emmy Award-winning senior writer for Moyers & Company and BillMoyers.com, a past senior writing fellow at the policy and advocacy group Demos, and former president of the Writers Guild of America East. Follow him on Twitter: @MichaelWinship.

I’m amazed, I must say. Seldom do I encounter a blog that’s equally educative and interesting, and without a doubt, you’ve hit the nail on the head. The problem is something that not enough people are speaking intelligently about. I am very happy that I found this in my hunt for something relating to this.|