Recently there was a fire on the train tracks of Chicago’s metro that demonstrated how useful cell phones are in an emergency.

Attention passengers—there has been a fire on the train tracks and firefighters are on their way to assist you,” said the PA system.

“There has been a fire on the train tracks and firefighters are on their way to assist us,” 40 people relayed into their cell phones.

“Please remain in your car until further instructions.”

“We’re remaining in our car until further instructions,” relayed 40 cell phone callers.

Passengers didn’t talk to each other and discuss, perhaps, opening the side doors. They didn’t demand a further and better explanation from train officials. They talked to the person who knows them as “It’s me.”

A week later, a driver, talking on his cell phone, almost struck a pedestrian also talking on her cell phone as she crossed the street. Both yelled at each other’s idiocy, which caused such a close call, but neither hung up. They were too busy telling the person on the other end what that &%$@ idiot almost did.

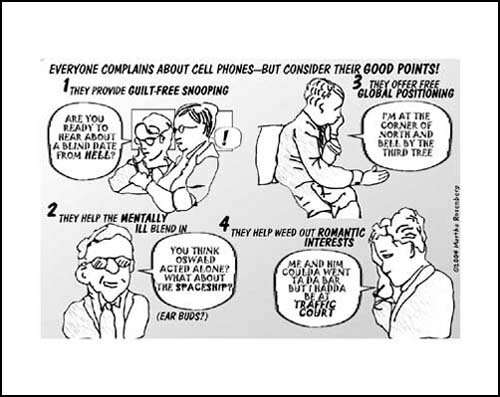

Cell phones are supposed to help communication but they also dodge communication. An informal survey on a college campus found the majority of incoming freshmen were using their cell phones to talk to—anybody?—Mom! . . . not to make new friends. Increasingly doctors post “no cell phones” signs in their offices, having spent too much of their valuable time listening to, “have you looked in the second drawer” while trying to examine a patient. And raise your hand if you’ve had lunch or dinner with someone who preferred their cell phone’s company to you? To them, it seemed more immediate.

Cell phones have been called the new cigarette because of their ubiquity and addictiveness (which has created a subcategory of cell-in-commode plumbing problems). When Roman Catholic bishops in Italy suggested people give up their cell phones for Lent, people said, essentially, we’re not that faithful.

And, speaking of the word “said,” what do cell phoners have against it? Why do they replace it with “all” (and I’m all what do you mean I’m late), “like” (I’m like what are you doing after work?) or “go” (So I go what are you doing and he goes . . . ) “Go” implies a demonstration or accompanying pantomime—yes, like almost getting hit by a car.

Why can’t they use colorful verbs like observed, retorted, suggested, reminded, conceded, cautioned, asserted or responded for “said” if we have to listen to them? Why don’t they talk about last night’s date, a bounced check or their roommate or boss from hell instead of boring us with “Hi, it’s me,” “I’ll be there in ten minutes,” and “I’m at State and Lake.”

Cell phones have been credited with helping emotionally disturbed people who talk to themselves blend in. But there are big differences. The conversation of emotionally disturbed people is usually more interesting, with a better narrative . . . and few would keep talking if they almost got hit by a car.

Martha Rosenberg will be interviewed on CSPAN2 this weekend about her new food and drug expose “Born with a Junk Food Deficiency” on Book TV’s After Words:

Martha Rosenberg will be interviewed on CSPAN2 this weekend about her new food and drug expose “Born with a Junk Food Deficiency” on Book TV’s After Words:

Saturday, July 7th at 10pm (ET)

Sunday, July 8th at 9pm (ET)

Monday, July 9th at 12am (ET)

Monday, July 9th at 3am (ET)