An article last week in the British Medical Journal finds that one egg per day is not associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease or stroke. That is good news for the egg industry and egg lovers—but it also contradicts several other studies.

An article last week in the British Medical Journal finds that one egg per day is not associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease or stroke. That is good news for the egg industry and egg lovers—but it also contradicts several other studies.

In 2008, the American Heart Association’s journal Circulation reported that just one egg a day increased the risk of heart failure in a group of doctors studied. And in 2010, an article in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology lamented the “widespread misconception . . . that consumption of dietary cholesterol and egg yolks is harmless.” The article further cautioned that “stopping the consumption of egg yolks after a stroke or myocardial infarction [heart attack] would be like quitting smoking after a diagnosis of lung cancer: a necessary action, but late.”

Heart disease isn’t the only health concern associated with eating eggs. According to studies in the journals Nutrition and Diabetes Care, eating eggs is “positively associated” with the risk of diabetes.

Eggs also have a link to ovarian cancer, says an article in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, and the culprit is not necessarily cholesterol. (The chicken egg has the highest cholesterol of any other foodstuff—packing approximately 275 mg of cholesterol—more than one day’s worth).

“It seems possible that eating eggs regularly is causally linked to the occurrence of a proportion of cancers of the ovary, perhaps as many as 40 percent, among women who eat at least 1 egg a week,” wrote the authors. In one study the article cites, three eggs per week increased ovarian-cancer mortality three-fold, compared with less than one egg per week.

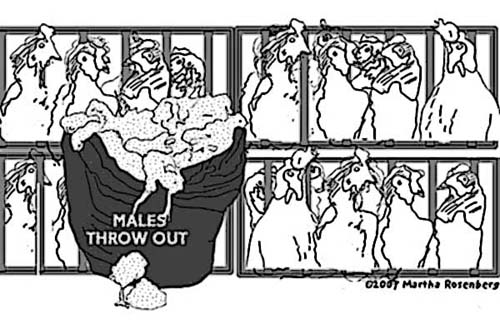

Eggs have also been assailed for their germ content, in addition to their nutritional content, thanks to their modern production methods—30,000 or more caged hens stacked on top of each other over their own manure. The FDA reports that egg operations are so festooned with salmonella and other bacteria that during inspections, it found a hatchery injecting antibiotics directly into the eggs of laying hens, presumably to take the offensive with germ control.

Would eggs from such antibiotic-treated hens also have antibiotic residues? Yes, says an article in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, which reports that “detectable residues were observed in eggs derived from enrofloxacin-treated hens” as well as “yolks from hens treated with enrofloxacin.”

Clearly there are more concerns about the safety of eggs and especially commercially produced eggs than those addressed in last week’s article in the British Medical Journal.

Martha Rosenberg is a freelance journalist and the author of the highly accalimed “Born With A Junk Food Deficiency: How Flaks, Quacks and Hacks Pimp The Public Health,” published by Prometheus Books.