Most people have heard of the drug companies Pfizer, Eli Lilly, and Merck. But they may not have heard of the animal-drug companies Fort Dodge, Elanco, or Intervet and the drugs they make. “Animal Pharma,” the animal-drug divisions within drug companies, tends to operate under the public’s radar. First, because the people who eat food grown with its products are not its actual customers and secondly because the additives, hormones, growth promoters, antiparasite and fungal drugs, and vaccines it uses would make people lose their appetites.

But Animal Pharma is a huge revenue engine that sells drugs by the ton, often with no prescription or veterinarian’s approval necessary, and it provides a never-ending supply of compliant patients. Unlike “people” Pharma, Animal Pharma requires little advertising or marketing against competing drugs, schmoozing of doctors, and sales calls, and it seldom experiences the safety scandals that plague drugs for people and reach Capitol Hill.

One reason for Animal Pharma’s growth is that contemporary, intensive factory farming is predicated on maximum output from each animal “unit” in confined spaces. For example, chickens were once slaughtered at fourteen weeks old, when they weighed about two pounds, but by 2001 they were slaughtered at seven weeks, when they weighed between four and six pounds. The continued efficiencies require high use of growth producing drugs, and drugs to treat and prevent diseases caused by crowding, stress, and immobility.

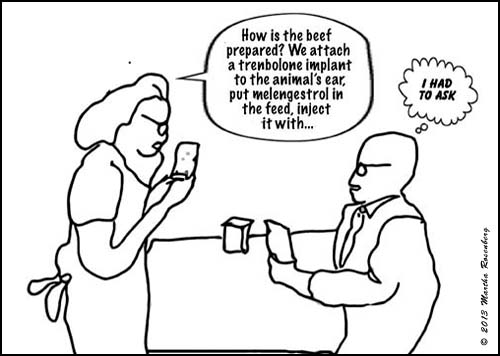

Few consumers could name one animal drug used to produce the food they are eating since the names don’t appear on labels (and would kill sales if they did.) And even though the organic-food movement and mad-cow scares have made people think about what their “meat eats”—look at the grass-fed-beef movement—they still don’t ask what drugs the animal ingested.

For example, who wants to eat an animal treated with the antibiotic tilmicosin? The drug label, intended for the farmer, says, “Not for human use. Injection of this drug in humans has been associated with fatalities.” Tilmicosin’s label even has an emergency phone number printed right on the bottle, as well as a note telling physicians what to do in case the farmer accidentally injects himself. (It says, “The cardiovascular system is the target of toxicity and should be monitored closely. Cardiovascular toxicity may be due to calcium channel blockade.”)

Yet tilmicosin is widely used in food animals and even shows up in the milk of treated dairy cows, according to a report from an Ohio TV station recently.

A 2010 Office of Inspector General (OIG) report found that Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) supervision of cattle was a farce—with some drug residues missed, others not tested for, and clearly contaminated meat left in the food supply. Among the drugs found in beef released to the public were penicillin; the antibiotics florfenicol, sulfamethazine, and sulfadimethoxine; the anti-parasite drug ivermectin, the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug flunixin; and heavy metals. Four plants had an astounding 211 drug residue violations, but repeat violators—”individuals who have a history of picking up dairy cows with drugs in their system and dropping them off at the plant”—are widely tolerated by the inspection service, says the report. Ninety percent of veterinary drug residue violations are found in dairy cows and calves, the report adds.

Clearly the absence of drugs listed on food packages doesn’t mean the drugs are absent in the product. And when Animal Pharma says the drugs are given for animal “health,” it is really the “health” of meat producers’ revenues. END

Find out more about veterinary drugs in foods in Martha Rosenberg’s acclaimed expose, Born with a Junk Food Deficiency: How Flaks, Quacks, and Hacks Pimp the Public Health.